图1

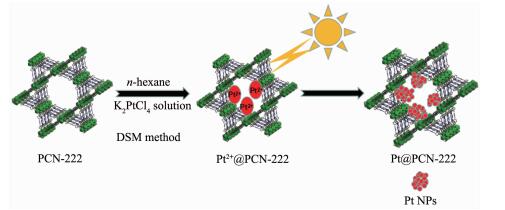

Schematic illustration for synthesis the photocatalyst Pt@PCN-222

Figure1.

Schematic illustration for synthesis the photocatalyst Pt@PCN-222

图1

Schematic illustration for synthesis the photocatalyst Pt@PCN-222

Figure1.

Schematic illustration for synthesis the photocatalyst Pt@PCN-222

铂纳米颗粒修饰的多孔卟啉基金属-有机框架化合物高效光催化产氢

English

Platinum Nanoparticle-Decorated Porous Porphyrin-Based Metal-Organic Framework for Photocatalytic Hydrogen Production

-

0 Introduction

Photocatalytic water splitting for hydrogen production is one of the biggest findings and attracts great research interests nowadays due to its potential ability in clean energy and renewable resources[1]. Efficient hydrogen production is dependent on the development of high-efficient catalysts, which could create electron-holes separation under light irradiation[2-4]. Of particular interest are the catalyst could efficiently utilize and adsorb the visible-light region of the sunlight. Furthermore, the active site in the efficient catalysts should be exposed for the accessible of the substrates as much as possible and thus reducing diffusion resistance. Compared with nonporous and microporous materials, mesoporous phtocatalysts are promising materials to solve this problem. Therefore, it is considerable to design and synthesize mesoporous materials that could harvest visible-light to promote efficiently photocatalytic water splitting for hydrogen production.

Over the past decade, metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) have emerged as promising materials for a variety of fields such as gas storage and separation, drug delivery, bioimaging, chemical sensing, and catalysis[5-6] due to their high surface areas, tunable pores, and functionalities[7-14]. In particular, the numerous metal centers and functional organic ligands could be selected to construct many unique porous MOFs thus making them as promising semiconductor materials for photocatalytic reactions, including water splitting and CO2 photoreduction. The judicious choice of functional ligands that act as antennas to absorb visible-light to produce photogenerated electron-hole pairs is particularly important to improve the efficiency under the irradiation of visible-light. Moreover, the microporous MOFs limits the diffusion of substrates and loading the active guest species such as metal nanoparticles. Therefore, it is highly urgent to synthesize mesoporous stable MOFs that could adsorb visible-light for efficient photocatalysis.

Porphyrins are one class of the most significant pigments to be found in nature. They have been widely used in light harvesting and catalysis owing to their structural robustness, strong aromaticity, rich metal coordination chemistry, attractive electronic, optical and electrochemical properties[15]. In addition, porphyrins could be used as building blocks to construct MOFs for catalysis and light harvesting[16]. Rosseinsky et al. prepared two porphyrin-based Al-MOFs, which shows low activity for the photocatalytic hydrogen-production due to the diffusion limitations of sacrificial agent in the micropores, as well as the difficult accessible of Pt nanoparticles. Therefore, choosing appropriate mesoporous porphyrin-based MOFs is benefit for improving the yield of hydrogen[17].

Notably, the introduction of metal nanoparticles (MNPs) with high Fermi energy level into the pores of MOFs could lead to enhanced photocatalysis because it can act as effective electron acceptors for charge separation and induce water splitting[18-20]. Noble-metal NPs, especially Pt NPs are frequently used as electron acceptors for promoting photocatalysis. However, only several examples of metal NPs/MOF composites have been applied for water splitting to produce hydrogen[1-2, 7, 34]. Moreover, compared to the conventional method for preparation of MNPs supported on MOFs including colloidal synthesis, chemical vapor deposition and incipient wetness impregnation[21-25], visible-light reduction instead of the use of the strong reducing agents such as NaBH4 is a milder method, which could maintain the structure of composite material[26]. PCN-222, pioneered by Zhou, is a meso-porous Zr-MOF based on porphyrin containing a large 1D open channel with a diameter of 3.7 nm. Therefore, herein, by using double-sovlent method followed by visible-light reduction, Pt NPs of ca. 2.5 nm were incorporated into the mesopores of PCN-222. The obtained mesoporous MOF composite Pt@PCN-222 can effectively adsorb visible-light to lead to the remarkably enhanced activities for photo-catalytic performance in H2 evolution reduction under visible-light irradiation (λ≥420 nm) due to the synergistic effect of semiconductor porous materials and Pt NPs.

1 Experimental

1.1 Materials and instruments

The reagents pyrrole, propionic acid, methyl 4-formylbenzoate, N, N-diethylformamide (DEF), N, N-dimethylformamide (DMF), benzoic acid, acetone, pot-assium tetrachloroplatinate (K2PtCl4), were purchased from Tansoole. Other reagents and solvents were obtained from commercial sources and used without further purification. 1H NMR spectra were recorded by a BrukerAvance Ⅲ spectrometer with 400 MHz. Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) patterns were performed on a Miniflex 600 diffractometer using Cu Kα radiation (λ=0.154 nm, 30 kV, 15 mA). The morphologies of catalysts were studied using a FEIT 20 transmission electron microscope (TEM) working at 200 kV. Noble metal content was measured by inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP-AES) on an Ultima 2 analyzer (Jobin Yvon). Gas sorption measurement was measured by a Micromeritics ASAP 2020 system at desired temperature. Valence state of element was measured by X-ray photoelectron spectro-scopy (XPS) on an ESCALAB 250Xi X-ray photo-electron spectrometer (Thermo Fisher) using an Al Kα source (15 kV, 10 mA). The UV-Vis diffuse reflectance spectra were carried out on a Perkin Elmer Lambda 900 UV/vis spectrometer equipped with an integrating sphere over the 200~800 nm wavelength range at room temperature with BaSO4 plate as reference material.

1.2 Synthesis of tetrakis(4-carboxyphenyl) porphyrin (H2TCPP)

The ligand H2TCPP was synthesized based on previous reports with minor modifications[27]. Typically, propionic acid (150 mL), pyrrole (9.0 g, 0.043 mol) and methyl p-formylbenzoate (20.7 g, 0.126 mol) were added in a 500 mL three necked flask and the solution was refluxed at 130 ℃ for 12 h. After the reaction mixture was cooled down to room temperature, crystals were washed with ethanol, ethyl acetate and THF, and then collect purple crystals by suction filtration. The obtained ester (1.95 g) was stirred and refluxed at 85 ℃ for 12 h in a 500 mL three necked flask by adding THF (60 mL) and MeOH (60 mL) and a solution of KOH (6.8 g, 120.4 mmol) in H2O (60 mL). After cooling down to room temperature, THF and MeOH were evaporated. Then plenty of water (2 L) was added into the solution and acidified with 1 mol·L-1 HCl until no further precipitate was detected. The violet solid was collected by filtration, washed with water and dried in vacuum to give 1.90 g of the purple product H2TCPP[28]. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) (Fig.S1): δ 13.30 (s, 4H), 8.87 (s, 8H), 8.39 (d, 8H), 8.35 (d, 8H), -2.94 (s, 2H).

1.3 Synthesis of PCN-222

PCN-222 was synthesized according to the literature[28]. In a typical experiment, ZrCl4 (50 mg) and benzoic acid (2 700 mg) were dissolved in 8 mL of DEF by ultrasonic 30 min, then, H2TCPP (50 mg) was added and ultrasonically dissolved adequately. The mixture was heated to 120 ℃ and hold this temperature for 48 h and then heat-up to 130 ℃ for 24 h. After cooling down to room temperature within 24 h, purple needle shaped crystals were harvested by filtration. The obtained as-synthesized PCN-222 was activated in 70 mL DMF containing 1 mL of concentrated hydrochloric acid at 120 ℃ for 12 h. The sample was followed by centrifuge and washed with DMF and acetone for several time and soaked in 100 mL acetone for 24 h. After the removal of acetone by centrifugation, the sample was dried in vacuum at 120 ℃ for 12 h.

1.4 Synthesis of Pt@PCN-222

The Pt2+ were loaded on PCN-222 by double solvent method[29]. Typically, 100 mg PCN-222 sample, which was pre-activating at 120 ℃ for 5 h, was added into 20 mL of dry n-hexane as hydrophobic solvent and sonicated for 30 min until the mixture dispersed uniformly. Then 54 μL of K2PtCl4 aqueous solution with suitable concentration as the hydrophilic solvent was dropwise added to the above suspension within 30 min under continuously vigorous stirred. After stirring for 5 h and removing n-hexane, the obtained Pt2+@PCN-222 was suspended in 40 mL ethanol and was reduced in the visible-light for 3 h, then washed with ethanol twice and dried in vacuum at 70 ℃ for further use. The Pt content was 1.01% (w/w) determined by ICP.

1.5 Photocatalytic hydrogen production

The photocatalytic hydrogen production experiments were carried out in a 200 mL quartz reactor under stirring at ambient cold bath temperature with a 300 W Xe lamp equipped as a visible-light source. 10 mg of the photocatalyst Pt@PCN-222 was dispersed in 90 mL deioned water with 10 mL triethanolamine (TEOA) as a sacrificial electron donor, then the suspension was evacuated several times to remove air, the reactant solution were fixed and irradiated by the Xe lamp. The contents of hydrogen gas was measured by gas chromatography (GC 7920 System) using a Thermal Conductivity detector (TCD) according to the standard curve.

2 Results and discussion

The mesoporous material PCN-222 based on porphyrin as a kind promising candidate for the efficiently photo-catalysis was synthesized by literature[1]. As shown in Fig. 1, K2PtCl4 was firstly loaded into the channels of PCN-222 via double solvent method based on its hydrophilic inner pores. Then, Pt@PCN-222 in which Pt NPs were successfully encapsulated was obtained by visible-light reduction (Fig. 1). The schematic illustration for the photocata-lytic hydrogen production process over Pt@PCN-222 is showed in Fig. 2. The materials were structurally characterized by a combination techniques including powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD), N2 adsorption-desorption, X-ray photoelectron spectrometer (XPS), inductive coupled plasma emission spectrometer (ICP), transmission electron microscope and UV-Vis diffuse reflectance spectra and electrochemical workstation.

图1

Schematic illustration for synthesis the photocatalyst Pt@PCN-222

Figure1.

Schematic illustration for synthesis the photocatalyst Pt@PCN-222

图1

Schematic illustration for synthesis the photocatalyst Pt@PCN-222

Figure1.

Schematic illustration for synthesis the photocatalyst Pt@PCN-222

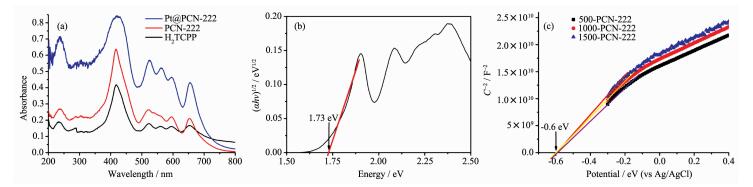

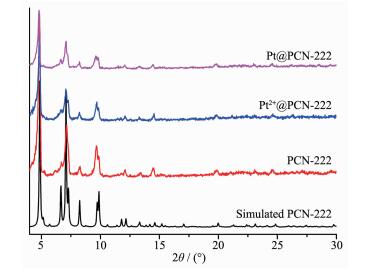

PXRD patterns (Fig. 3) show that the peaks of the as-synthesized porphyrinic MOF are matched well with those of the simulated PCN-222, confirming the formation of Pt@PCN-222. After loading Pt2+ (ca. 1.01%, w/w), the peaks intensity of PCN-222 becomes weak, implying that the frameworks of PCN-222 are partly amorphous. This is ascribed to the low mechanical stability and drying process[30]. The characteristic peak of Pt(111) is indistinguishable owing to the low Pt loading amount and the well-dispersed small Pt NPs.

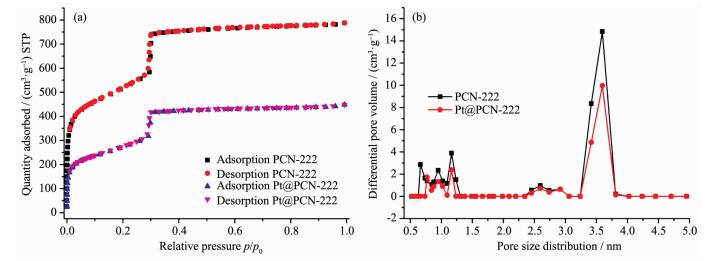

The N2 adsorption isotherms of PCN-222 at 77 K show its N2 uptake and Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) surface area are 790 cm3·g-1 (STP) and 2 060 m2·g-1, respectively. The calculated total pore volume of PCN-222 is as high as 1.219 cm3·g-1. The pore size distribution (PSD) calculated from the density functional theory (DFT) method (Fig. 4b) shows a mesopre with 3.7 nm, which is identified with the crystal structure of PCN-222. After loading Pt NPs, the N2 uptake and BET surface area of the composite Pt@PCN-222 are decreased to 420 cm3·g-1 and 1 144 m2·g-1, respectively. Although the pores of PCN-222 are partly occupied by Pt NPs, its mesopores centered at 3.7 nm are still maintained which will facilitate the diffusion of the water and sacrificial agent.

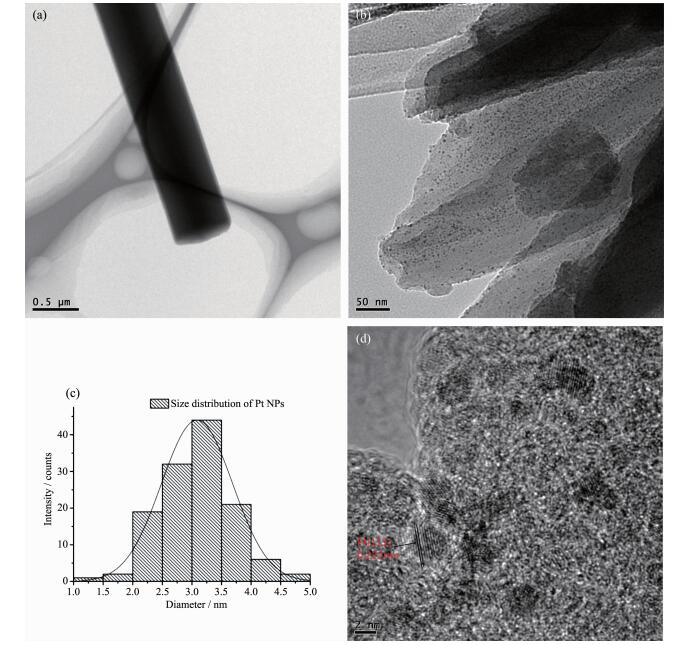

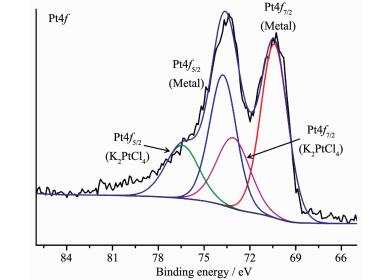

The TEM images (Fig. 5) show that most of Pt NPs with a uniform size of around 2.5 nm are well dispersed and successfully encapsulated in the pores of the PCN-222. The HRTEM image in Fig. 5d unambiguously shows the characteristic lattice fringes of 0.22 nm, which can be indexed as the (111) planes of the Pt NPs[31-32]. XPS measurements show that the peaks of 71.1, 74.5 eV are ascribed to Pt(0) (Fig. 6), while the other two peaks at 72.3, 75.6 eV are observed indicating that ca. 40% (w/w) Pt2+ are retained[33]. ICP-AES indicates that the loadings of Pt in Pt@PCN-222 is about 1.01% (w/w).

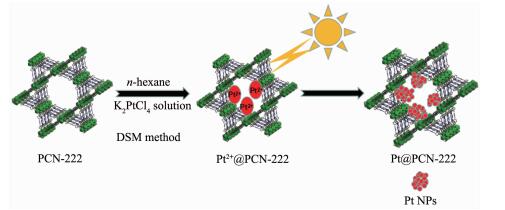

The UV-Vis diffuse reflectance spectra for PCN-222 and Pt@PCN-222 show strong adsorption in the region of 350~800 nm, which are similar with that of H2TCPP ligand (Fig. 7a). The band gap of the samples is approximately 1.73 eV based on the Tauc plot (Fig. 7b). The results imply that the MOF materials based on porphyrin groups indeed have photon absorption and electron-hole separation ability upon visible-light light irradiation. The positive slopes of Mott-Schottky plots for PCN-222 at different frequencies of 500, 1 000, and 1 500 Hz indicate that it is an n-type semiconductor (Fig. 7c). The flat band position determins from the intersection is -0.60 V vs Ag/AgCl, thus the LUMO of PCN-222 is estimated to be -0.40 V vs normal hydrogen electrode (NHE). The semiconductor character of PCN-222 makes it benefit in photoreduction and photocatalysis reaction.

图7

(a) UV-Vis diffuse reflectance spectra of H2TCPP, PCN-222, Pt@PCN-222; (b) Tauc plot of PCN-222;

(c) MottSchottky plots for PCN-222 in 0.2 mol·L-1 Na2SO4 aqueous solution and corresponding LUMO

Figure7.

(a) UV-Vis diffuse reflectance spectra of H2TCPP, PCN-222, Pt@PCN-222; (b) Tauc plot of PCN-222;

(c) MottSchottky plots for PCN-222 in 0.2 mol·L-1 Na2SO4 aqueous solution and corresponding LUMO

图7

(a) UV-Vis diffuse reflectance spectra of H2TCPP, PCN-222, Pt@PCN-222; (b) Tauc plot of PCN-222;

(c) MottSchottky plots for PCN-222 in 0.2 mol·L-1 Na2SO4 aqueous solution and corresponding LUMO

Figure7.

(a) UV-Vis diffuse reflectance spectra of H2TCPP, PCN-222, Pt@PCN-222; (b) Tauc plot of PCN-222;

(c) MottSchottky plots for PCN-222 in 0.2 mol·L-1 Na2SO4 aqueous solution and corresponding LUMO

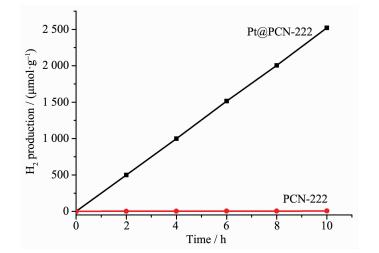

Considering that the Pt@PCN-222 materials have broad adsorption in UV-Vis region and electron acceptor effect, water-splitting H2 evolution was investigated under visible-light light. The reaction vessel with reacting solution irradiated for 10 h. The time course of H2 evolution for Pt@PCN-222 is shown in Fig. 8. Pt@PCN-222 displays highly efficient H2-evolution activity of 253 μmol·h-1·g-1, which surpassed some of other reported Pt/MOFs catalysts (Table S1)[1, 17, 34]. It should be noted that the support PCN-222 shows nearly no activity.

3 Conclusions

In summary, well-dispersed Pt NPs of ca. 2.5 nm were successfully encapsulated in the mesopores of porphyrin-based MOF PCN-222 via double solvent method followed by photoreduction. The obtained mesoporous MOF composite Pt@PCN-222 can effectively adsorb visible-light to promote the water splitting for hydrogen production, which gives a H2 yield of 253 μmol·g-1·h-1. The enhanced activity for water splitting to produce hydrogen is due to a broad visible-light absorption region of porphyrin functional groups in mesoporous PCN-222.

-

-

[1]

Xiao J D, Shang Q C, Jiang H L, et al. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 2016, 55:9389-9393 doi: 10.1002/anie.201603990

-

[2]

Chen Y F, Tan L L, Su C Y, et al. Appl. Catal., B, 2017, 206:426-433 doi: 10.1016/j.apcatb.2017.01.040

-

[3]

Zhang G G, Lan Z A, Wang X C. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 2016, 55:15712-15727 doi: 10.1002/anie.201607375

-

[4]

Wang C, deKrafft K E, Lin W B, et al. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2012, 134:7211-7214 doi: 10.1021/ja300539p

-

[5]

Wang X L, Tang Y J, Lan Y Q, et al. ChemSusChem, 2017, 10:2402-2407 doi: 10.1002/cssc.201700276

-

[6]

Han X, Liu Y, Cui Y, et al. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2017, 139: 8693-8697 doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b04008

-

[7]

Huang Y B, Liang J, Cao R, et al. Chem. Soc. Rev., 2017, 46:126-157 doi: 10.1039/C6CS00250A

-

[8]

Huang Y B, Wang Q, Cao R, et al. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2016, 138:10104-10107 doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b06185

-

[9]

Liu X, He L, Tang Z, et al. Adv. Mater., 2015, 27:3273-3277 doi: 10.1002/adma.v27.21

-

[10]

Zhao Y, Kornienko N, Yaghi O M, et al. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2015, 137:2199-2202 doi: 10.1021/ja512951e

-

[11]

Sun J S, Han Y F. RSC Adv., 2017, 7:22855-22859 doi: 10.1039/C7RA03033A

-

[12]

Yuan G Z, Rong L L, Wei X W, et al. CrystEngComm, 2013, 15:7307-7314 doi: 10.1039/c3ce40348c

-

[13]

Liu H, Chang L, Li Y, et al. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 2016, 55:5019-5023 doi: 10.1002/anie.v55.16

-

[14]

Li J R, Sculley J, Zhou, H C, et al. Chem. Rev., 2012, 112: 869-932 doi: 10.1021/cr200190s

-

[15]

沙秋月, 袁雪梅, 徐海军, 等.无机化学学报, 2016, 32:1293-1302 doi: 10.11862/CJIC.2016.166SHA Qiu-Yue, YUAN Xue-Mei, XU Hai-Jun, et al. Chinese J. Inorg. Chem., 2016, 32:1293-1302 doi: 10.11862/CJIC.2016.166

-

[16]

罗云, 史永平, 李珺, 等.无机化学学报, 2012, 28:1139-1144 http://www.wjhxxb.cn/wjhxxbcn/ch/reader/view_abstract.aspx?flag=1&file_no=20120610&journal_id=wjhxxbcnLUO Yun, SHI Yong-Pin, LI Jun, et al. Chinese J. Inorg. Chem., 2012, 28:1139-1144 http://www.wjhxxb.cn/wjhxxbcn/ch/reader/view_abstract.aspx?flag=1&file_no=20120610&journal_id=wjhxxbcn

-

[17]

Alexandra F, Matthew J R. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 2012, 51: 7440-7444 doi: 10.1002/anie.201202471

-

[18]

Zhou W, Li T, Jiang B J, et al. Nano Res., 2014, 7:731-742 doi: 10.1007/s12274-014-0434-y

-

[19]

Hua Q, Shi F C, Huang W X, et al. Nano Res., 2011, 4:948-962 doi: 10.1007/s12274-011-0151-8

-

[20]

Zhou X M, Liu G, Fan W H, et al. J. Mater. Chem., 2012, 22:21337-21354 doi: 10.1039/c2jm31902k

-

[21]

Meilikhov M, Yusenko K, Fischer R A, et al. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem., 2010, 10:3701-3714 doi: 10.1002/ejic.201000473/full

-

[22]

Hou C, Zhao G F, Li Y D, et al. Nano Res., 2014, 7:1364-1369 doi: 10.1007/s12274-014-0501-4

-

[23]

Jiang H L, Liu B, Xu Q, et al. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2009, 131:11302-11303 doi: 10.1021/ja9047653

-

[24]

Cheon Y E, Suh M P. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 2009, 48: 2899-2903 doi: 10.1002/anie.200805494

-

[25]

El-Shall M S, Abdelsayed V, Reich T E, et al. J. Mater. Chem. A, 2009, 19:7625-7631 doi: 10.1039/b912012b

-

[26]

马涛, 刘陶陶, 曹荣, 等.无机化学学报, 2014, 3:127-133 http://www.wjhxxb.cn/wjhxxbcn/ch/reader/view_abstract.aspx?flag=1&file_no=20140114&journal_id=wjhxxbcnMA Tao, LIU Tao-Tao, CAO Rong, et al. Chinese J. Inorg. Chem., 2014, 3:127-133 http://www.wjhxxb.cn/wjhxxbcn/ch/reader/view_abstract.aspx?flag=1&file_no=20140114&journal_id=wjhxxbcn

-

[27]

Feng D, Chung W C, Zhou H C, et al. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2013, 135:17105-17110 doi: 10.1021/ja408084j

-

[28]

Feng D, Gu Z Y, Zhou H C, et al. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 2012, 51:10307-10310 doi: 10.1002/anie.201204475

-

[29]

Zhu Q L, Li J, Xu Q. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2013, 135:10210-10213 doi: 10.1021/ja403330m

-

[30]

Mondloch J E, Hupp J T, Farha O K, et al. Chem. Commun., 2014, 50:8944-8946 doi: 10.1039/C4CC02401J

-

[31]

Zheng Z K, Huang B B, Whangbo M H, et al. J. Mater. Chem. A, 2011, 21:9079-9087 doi: 10.1039/c1jm10983a

-

[32]

Zhang N, Liu S Q, Xu Y J, et al. J. Phys. Chem. C, 2011, 115:9136-9145 doi: 10.1021/jp2009989

-

[33]

Su F B, Poh C K, Lin J Y. Energy Fuels, 2010, 24:3727-3732 doi: 10.1021/ef901275q

-

[34]

Guo W W, Lü H J, Hill C L. J. Mater. Chem. A, 2016, 4: 5952-5957 doi: 10.1039/C6TA00011H

-

[1]

-

-

扫一扫看文章

扫一扫看文章

计量

- PDF下载量: 18

- 文章访问数: 2392

- HTML全文浏览量: 476

下载:

下载:

下载:

下载: