图1

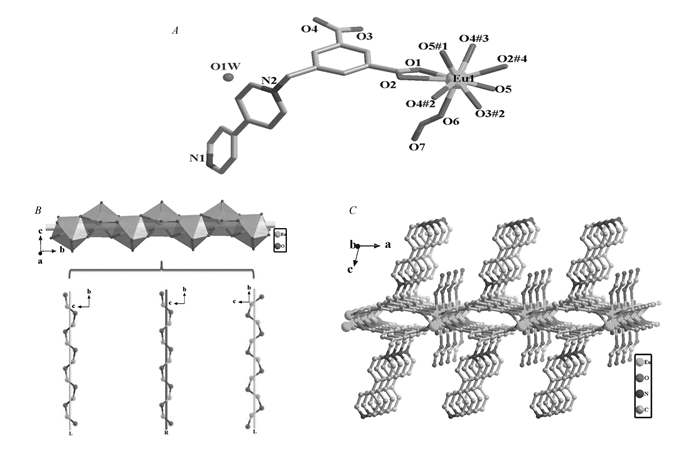

(A)The asymmetric unit of complex 1. Symmetry codes:#1.-x+2, y+1/2, -z; #2.-x+2, y-1/2, -z; #3.-x+1, y-1/2, -z; #4.x+1, y, z; #5.x-1, y, z; #6.-x+1, y+1/2, -z.(All hydrogen atoms and solvent molecules are omitted for clarity). (B)View of the three co-axial helical chains of the 1D rod-like chain in 1. (C)The two-dimensional layer structure viewed from b direction with the pyridinium rings hanging up and down the plane

Figure1.

(A)The asymmetric unit of complex 1. Symmetry codes:#1.-x+2, y+1/2, -z; #2.-x+2, y-1/2, -z; #3.-x+1, y-1/2, -z; #4.x+1, y, z; #5.x-1, y, z; #6.-x+1, y+1/2, -z.(All hydrogen atoms and solvent molecules are omitted for clarity). (B)View of the three co-axial helical chains of the 1D rod-like chain in 1. (C)The two-dimensional layer structure viewed from b direction with the pyridinium rings hanging up and down the plane

图1

(A)The asymmetric unit of complex 1. Symmetry codes:#1.-x+2, y+1/2, -z; #2.-x+2, y-1/2, -z; #3.-x+1, y-1/2, -z; #4.x+1, y, z; #5.x-1, y, z; #6.-x+1, y+1/2, -z.(All hydrogen atoms and solvent molecules are omitted for clarity). (B)View of the three co-axial helical chains of the 1D rod-like chain in 1. (C)The two-dimensional layer structure viewed from b direction with the pyridinium rings hanging up and down the plane

Figure1.

(A)The asymmetric unit of complex 1. Symmetry codes:#1.-x+2, y+1/2, -z; #2.-x+2, y-1/2, -z; #3.-x+1, y-1/2, -z; #4.x+1, y, z; #5.x-1, y, z; #6.-x+1, y+1/2, -z.(All hydrogen atoms and solvent molecules are omitted for clarity). (B)View of the three co-axial helical chains of the 1D rod-like chain in 1. (C)The two-dimensional layer structure viewed from b direction with the pyridinium rings hanging up and down the plane

紫精修饰多功能Eu(Ⅲ)配合物的荧光开关、非线性光学和光电活性

English

Multi-Functional Viologen-Based Eu(Ⅲ) Complex with Photoswitchable Luminescence, Nonlinear Optical Properties and Photovoltaic Activity

-

Multifunctional hybrid materials have been well explored for decades, because of their potential applications in information storage, molecular switches, sensing, energy conversion, etc[1-9]. In the process of constructing these multifunctional hybrid materials, the self-assembly of crystal engineering has become a preferred choice. Selectively combining functional organic ligands with different center metal ions to construct metal-organic framework(MOF) hybrid materials provides a versatile platform for synthesizing multifunctional materials with desirable properties[10-13]. Thereinto, choosing the suitable functional organic linkers seems especially important.

In recent years, viologen-based metal-organic complexes have caught much attention[14-27]. Mainly due to the electron-deficiency of the viologen groups, which exhibits excellent charge-transfer and redox properties with photoactivity[18]. And their versatile applications in selective guest adsorption[19-22], photochromism[23], photomodulated luminescence[24-25], mechanochromic luminescence[26], molecular recognition and sensing[27] are highly appreciated. Moreover, color-changing materials modulated by external stimuli, such as light, temperature, pH, electricity and mechano-/piezo-pressure, etc[28-32], are particularly tempting and may have more extensive practical/potential applications, such as protection, decoration, display, memory, switches, photography, and so on[28-34]. These make the research on this kind of hybrid material a hot topic. Therefore, it is of great importance to explore the synthesis strategy and the structure-property relationship of this kind of multi-functional metal-organic hybrid material.

During the pursuit of synthesizing new photochromic MOF hybrid materials, viologen-functionalized aromatic carboxylate derivatives have been chosen as functional organic ligands because of their excellent features:ⅰ)multidentate bridging ligand with N-and O-donors has good coordination capability; ⅱ)carboxyl group can adopt various coordination modes to show flexible coordination arrangements with central metal atoms; ⅲ)multiple aromatic rings can offer additional π-π interactions for electron transfer. Thus, series of such kind of multi-functional solid-state MOF materials have been successively reported, and they exhibit interesting multi-switchable features including photochromism, photomodulated luminescence, photoswitchable nonlinear optical(NLO) and piezoelectric properties, etc[35-36]. However, some influential factors, such as the molecular structure as well as the packing type, distance and orientation between the electron donor and the electron acceptor that affect the rate of the electron change reactions as well as properties are very complicated and still unclear up to now[37-39]. Therefore, much more works are needed to probe the relationship between the crystal structures and photoresponse properties of this kind of MOF material.

Inspired by the foregoing statements, we utilized a viologen-functionalized aromatic dicarboxylate ligand 1-(3, 5-dicarboxybenzyl)-4, 4′-bipyridinium nitrate(H2L+NO3-) to react with Eu(Ⅲ) in the presence of solvent dimethylformamide(DMF) and afford a new complex {[Eu(μ2-OH)(L)(HCO2)]·H2O}n(1), with the formate anions resulting from the in situ decomposition of DMF solvent molecules during the synthesis. Complex 1 is chiral and displays a two-dimensional layer structure. It manifests fast photoresponsibility and reversibility. Moreover, the title complex shows the multifunctionality of photoresponse luminescence, photoswitchable second-harmonic generation(SHG)-activity, as well as photomodulated photovoltaic activity.

1 Experimental

1.1 Materials and methods

1-(3, 5-Dicarboxybenzyl)-4, 4′-bipyridinium chloride(H2L+NO3-) ligand was prepared according to the reported procedure[36].All other commercially available reagents are of reagent grade quality and purchased from Aladdin Industrial Corporation. Elemental analyses for C, H and N were determined using a Perkin-Elmer 240 elemental analyzer(PerkinElmer, USA). Powder X-ray diffraction(PXRD) patterns for complex 1 was recorded on a Rigaku D/max-3B diffractometer(CuKα, λ=0.15418 nm) radiation(Rigaku, Japan) over the 2θ range of 5°~50° with a scan speed of 5°/min at room temperature. Thermogravimetric analyses were performed using a TA Q50 thermal analyzer(TA Instruments, USA) in the temperature range of 30 to 800 ℃ with a heating rate of 10 ℃/min under nitrogen flow. UV-Vis diffuse reflectance spectra were measured on an Agilent Cary 5000 UV-VIS-NIR Spectrophotometer(Agilent, USA) with BaSO4 as the reference. Electron-spin resonance(ESR) signals were recorded on a Brucker A300 spectrometer(Brucker, Germany) at room temperature. The solid-state luminescence spectra were recorded on a Hitachi 850 fluorescence spectrophotometer(Hitachi, Japan). Powder SHG measurement on the sample was performed on a modified Kurtz-NLO system using 1064 nm laser radiation(VIBRANT HE 355 LD, USA). The SHG signal was detected using a CCD detector. Surface photovoltage spectroscopy(SPS)(PerfectLight, China) was measured on a home-built apparatus, which consisted of a lock-in amplifier(SR830-DSP), and a light chopper(SR540), a sample cell, a 500 W xenon lamp and a double-grating monochromator(Zolix SP500). In the photovoltaic cell, the powder sheet was directly sandwiched between two blank indium tin oxide(ITO) electrodes.

1.2 Synthesis of {[Eu(μ2-OH)(L)(HCO2)]·H2O}n(1)

The reaction mixture containing Eu(NO3)3·6H2O(0.0130 g, 0.029 mmol), H2L+NO3-(0.0110 g, 0.030 mmol), DMF(1 mL) and water(1 mL) was sealed in a 25 mL Teflon reactor autoclave and heated to 120 ℃ for 3 days. After cooling down to room temperature at a rate of 5 ℃/h, pale-yellow crystals suitable for single crystal X-ray crystallographic analysis were obtained in 73% yield based on Eu. Anal. Calcd. for {[Eu(μ2-OH)(L)(HCO2)]·H2O}n:H 3.20%, C 38.15%, N 6.92%. Found:H 3.25%, C 38.20%, N 6.85%.

1.3 X-ray crystallography

Single crystal X-ray analysis was conducted on a Bruker SMART APEX CCD diffractmeter using graphite-monochromatized MoKα radiation(λ=0.071073 nm) at room temperature using the ω-scan technique. Lorentz polarization and absorption corrections were applied. The structure was solved by direct methods with SHELXS-97[40-41] and refined by full-matrix least-squares using the SHELXL-97[42] program. All non-hydrogen atoms were refined anisotropically. The hydrogen atoms of the ligand were included in the structure factor calculation at idealized positions using a riding model and refined isotropically. The hydrogen atoms of the solvent water molecules were located from the difference Fourier maps, and then restrained at fixed positions and refined isotropically. The crystallographic data and selected bond distances and angles for complex 1 are listed in Tables S1 and S2(Supporting Information).

2 Results and discussion

2.1 Synthesis of {[Eu(μ2-OH)(L)(HCO2)]·H2O}n(1)

We have reported a structural similar Eu-MOF:{[Eu(μ2-OH)(L)(H2O)]·NO3·H2O}n, constructed by the same ligand but using different reaction solvents. Interestingly, when the solvent dimethylformamide(DMF) was used instead of CH3CN, the formate anions(HCO2) generated from the in situ decomposition of DMF molecules under high temperature. Moreover, the in situ formed HCO2 participates in coordinating with the central metal ions to replace the coordinated aqua ligands. The CCDC reference number of complex 1 is 1523149.

2.2 Crystal Structure of {[Eu(μ2-OH)(L)(HCO2)]·H2O}n(1)

X-ray structural analysis revealed that complex 1 crystallizes in the chiral space group P21. The asymmetric unit involves a crystallographically independent Eu(Ⅲ) ion, a μ2-OH-, an anionic L- ligand, a formate anion, and a solvated water molecule. The central Eu(Ⅲ) is nona-coordinated by nine oxygen atoms, in which the six oxygen atoms(O1, O2, O3#2, O4#2, O2#4, O4#3) come from the carboxylate groups of four different L- ligands, two from the coordinated μ2-OH- anions(O5, O5#1) and the other one from the HCO2 group, completing a twisted capped square antiprismatic coordination sphere(Fig. 1A). The HCO2 anionic units originate from the in situ decomposition of dimethylformamide(DMF) solvent molecules during the synthesis. The Eu—O bond lengths range from 0.2369(5) to 0.2653(5) nm, are in accordance with those of the reported europium-oxygen complexes. As for the L- ligands, the N atom of the pyridinium rings doesn′t participate in coordination, only the oxygen atoms of the carboxylate groups take part in coordinating in μ4-η1-η2-η1-η2-manner. The neighbouring Eu(Ⅲ) ions are connected by the aromatic carboxylate groups and the μ2-OH- bridges to form a rod-like one-dimensional chain extending along b direction with the adjacent EuEu distance of 0.37967(2) nm(Fig. 1B). It should be noted that the Eu(Ⅲ) ions are not in a straight line along the 1D rod-like chain, and each rod-like chain features three co-axial helical chains, with one being right-handed, and the other two left-handed(Fig. 1B). Furthermore, depending on the bridging of the aromatic carboxylate groups of the V-shaped ligand L-, these chiral helix chains are extended into 2D along ab plane, with the uncoordinated bipyridinium rings and the coordinated formate groups hanging up and down the ab plane(Fig. 1C).

图1

(A)The asymmetric unit of complex 1. Symmetry codes:#1.-x+2, y+1/2, -z; #2.-x+2, y-1/2, -z; #3.-x+1, y-1/2, -z; #4.x+1, y, z; #5.x-1, y, z; #6.-x+1, y+1/2, -z.(All hydrogen atoms and solvent molecules are omitted for clarity). (B)View of the three co-axial helical chains of the 1D rod-like chain in 1. (C)The two-dimensional layer structure viewed from b direction with the pyridinium rings hanging up and down the plane

Figure1.

(A)The asymmetric unit of complex 1. Symmetry codes:#1.-x+2, y+1/2, -z; #2.-x+2, y-1/2, -z; #3.-x+1, y-1/2, -z; #4.x+1, y, z; #5.x-1, y, z; #6.-x+1, y+1/2, -z.(All hydrogen atoms and solvent molecules are omitted for clarity). (B)View of the three co-axial helical chains of the 1D rod-like chain in 1. (C)The two-dimensional layer structure viewed from b direction with the pyridinium rings hanging up and down the plane

图1

(A)The asymmetric unit of complex 1. Symmetry codes:#1.-x+2, y+1/2, -z; #2.-x+2, y-1/2, -z; #3.-x+1, y-1/2, -z; #4.x+1, y, z; #5.x-1, y, z; #6.-x+1, y+1/2, -z.(All hydrogen atoms and solvent molecules are omitted for clarity). (B)View of the three co-axial helical chains of the 1D rod-like chain in 1. (C)The two-dimensional layer structure viewed from b direction with the pyridinium rings hanging up and down the plane

Figure1.

(A)The asymmetric unit of complex 1. Symmetry codes:#1.-x+2, y+1/2, -z; #2.-x+2, y-1/2, -z; #3.-x+1, y-1/2, -z; #4.x+1, y, z; #5.x-1, y, z; #6.-x+1, y+1/2, -z.(All hydrogen atoms and solvent molecules are omitted for clarity). (B)View of the three co-axial helical chains of the 1D rod-like chain in 1. (C)The two-dimensional layer structure viewed from b direction with the pyridinium rings hanging up and down the plane

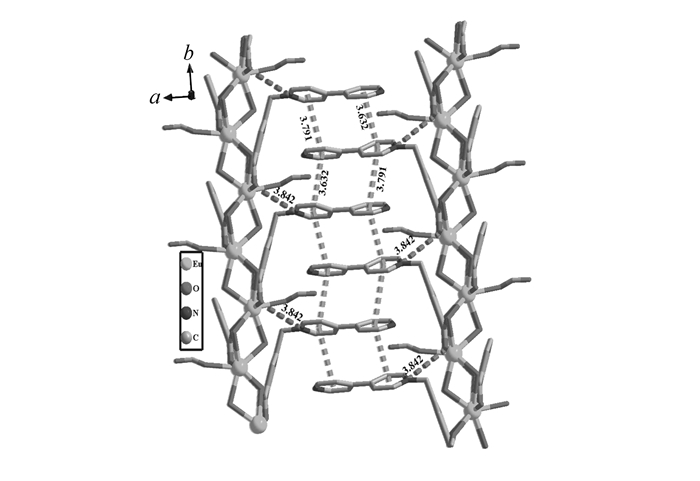

And along b direction, the hanging bipyridinium rings are strictly parallel to each other and the distances between the adjacent pyridinium rings are 0.3632 and 0.3791 nm, respectively, indicating the existence of the face-to-face π...π interactions. In addition, the lattice water molecules distributed among the layers, and formed hydrogen bonds with carboxyl and formate oxygen atoms, which could enhance the stability of the 3D solid-state structure of complex 1(Fig.S1 in Supporting Information).

2.3 Photochromic properties

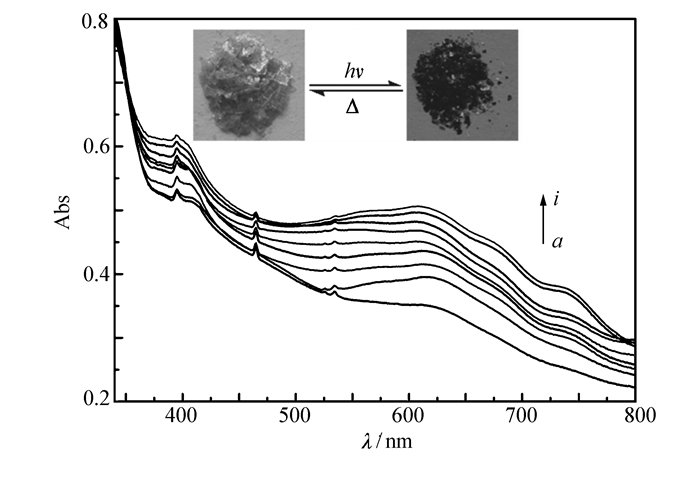

Complex 1 is photoactive and undergoes an obvious color change from pale-yellow to dark green in response to sunlight or 300 W Xenon lamp at ambient temperature in air. The colored photoproduct can be completely decolored by standing overnight at room temperature or annealing in air at 80 ℃ for 30 min, as shown in Fig. 2. The development and fading of the color can be repeated many times and no degradation of the efficiency in the color change of the crystals was observed.

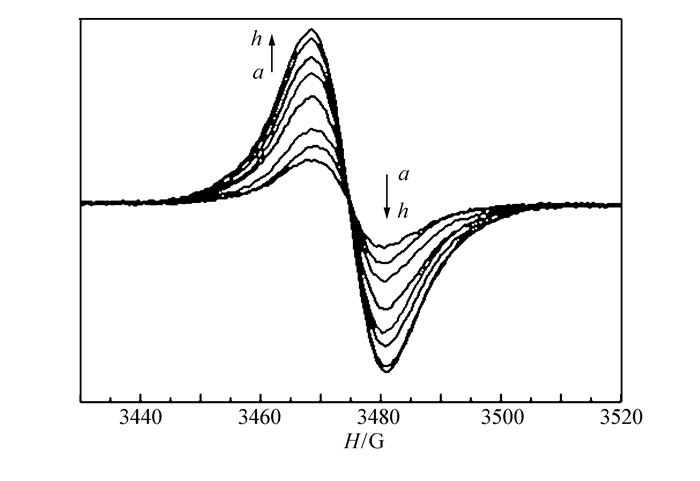

The UV-Vis diffuse reflectance spectra of the viologen-based complex 1 before and after photoirridiation are shown in Fig. 2. From Fig. 2, we can observe that with the duration of the irridiation time, two characteristic broad bands around 404 and 616 nm emerge in the UV-Vis diffuse reflectance spectra after coloration. And with the increasing of the irradiation time, the intensity raises, which suggests that the color change of complex 1 presumably arises from generation of the viologen radicals in the compound[43-44]. And the new bands tend to saturate after irradiation for 20 min. It is well documented in the literature that under suitable conditions the viologen moiety can undergo one electron transfer and convert into viologen radicals. This viologen radical bears a characteristic electron spin resonance(ESR) signal in the g=2.002~2.004 region, originating from the unpaired electron[45]. Thus, ESR study(Fig. 3) was carried out to make sure the presence of electron transfer during photoirradiation treatment. Complex 1 shows a very weak signal at g=2.0017 before irradiation, which may be ascribed to the presence of residual radicals. After irradiation, the signal at the same position is dramatically increased in intensity, confirming the formation of radicals. These values are close to that of a free electron(2.0023) and in accordance with previous reports for the viologen species[46-48]. The result furthermore demonstrated that the photochromic processes arise from photoinduced free radical generation of the viologen units[8, 12, 35-36].

From the viewpoint of the structure, for the viologen-based complexes, the electron transfer in the solid state is related to the short contact between the pyridinium N atom and the carboxylate O donor[49], and the face-to-face aromatic π....π interactions between the pyridinium rings can also provide an effective pathway for the electron transfer[23-24, 35-36]. A detailed analysis on the structure of the complex is helpful for us to understand the relationship between the structure and photochromic behavior. For complex 1, the formation of organic radical can be explained by single electron transfer from oxygen atoms of the carboxylate groups to pyridinium rings. Therefore, the organic component aromatic dicarboxylates play an important role on the photochromic properties:it may not only be a powerful factor to stabilize the viologen monocation radical, but also act as an important path for electron transfer from the π-conjugated substituent to the viologen cation in the photochromic process. What′s more, the close condensed packing mode makes the intramolecular electron transfer more facilitative and results in a viologen radical with dark-green color[50]. In the solid-state structure of complex 1, the shortest distance between the oxygen atom of the carboxyl groups and the nitrogen atom of the pyridinium rings is 0.3842 nm, and the highly ordered π....π interactions between the bipyridinium rings along b direction are 0.3632 and 0.3791 nm, respectively(Fig. 4). All these values are a little bigger than those of the previous reported Eu-MOF(0.3744 nm for the O....N distances; 0.3576 and 0.3776 nm for the π....π interactions between the adjacent bipyridinium rings), which may be explained by the bigger steric hindrance effect of the coordinated formate anion than that of the aqua ligand. But these values are still in favor of the intermolecular charge transfer between the carboxylate group donor and the viologen acceptor unit[51], and offer a reasonable electron-transfer pathway for the photochromic process[52]. Except the distance and orientation between donor atoms and acceptors in the solid state, the tilt angle between the two pyridinium rings may also affect the efficiency of the photoinduced reduction[53]. It is proposed that the planar configuration of two pyridinium rings are more favorable for the photoinduced reduction of viologens and the stability of free radicals[23], as the distortion between the intraligand pyridinium rings may destroy the large conjugated planar configuration, leading to a decrease in the stability of free radicals. The tilt angle between the pyridinium rings in complex 1 is 30.9°, which is close to that of the reported Eu-MOF(32.7°). These tilt angles are all suitable for formation of stable photo-generated radicals. The disparity of the photochromic behaviors between the two MOFs may come from the different distances from the donors to the acceptors. The little longer O....N distances and the π....π interactions of complex 1 compared with those of Eu-MOF lead to the free radicals of Eu-MOF more stable than that of complex 1. As a consequence, the colored crystal 1 is easier to revert to its initial state in air atmosphere in the dark or annealing, and presents fast-response to external stimuli as photo and thermal. Thus, the structural characteristics significantly influence the resulting photochromic properties.

From the results we can conclude that the structural and chemical properties make viologen-based aromatic dicarboxylate derivatives desirable candidates for host-guest interactions, in particular donor-acceptor charge-transfer type complexes[14]. Therefore, embedding the viologen-based aromatic dicarboxylate derivative into a condensed metal organic framework is an effective way to obtain photoresponse color changing materials.

2.4 Thermostability and PXRD pattern of complex 1

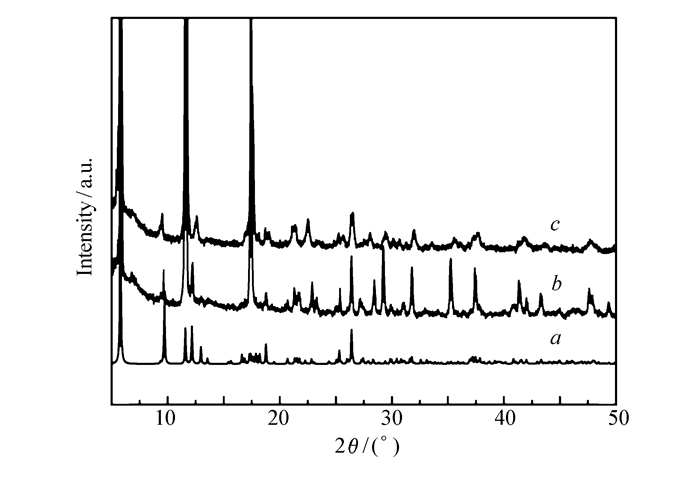

To characterize the phase purity and stability of the title compound more fully, powder X-ray diffraction(PXRD) and IR were performed on complex 1. The PXRD and IR patterns after the irradiation and after several coloring/bleaching cycles agree well with the data before irradiation(Fig. 5 and Fig.S2), suggesting that the crystal and molecular structure remains intact and has no photo-induced dissociation or rearrangement reactions happened during the reversible process.

In order to investigate the thermal stability of the title compound, the thermogravimetric analysis(TGA) was also determined(see Fig.S3 in Supporting Information). For complex 1, the first step of mass loss on the TGA curve occurs from ca. 60 to 125 ℃(obsd. 3.32%; calcd. 3.20%), corresponding to the departure of the guest water molecule and then followed by the leave of the μ2-OH group up to 155 ℃(obsd. 3.14%; calcd. 3.01%). The next weight loss in the range of 155 to 212 ℃ corresponds to the decomposition of the formate anion(obsd. 7.89%; calcd. 7.97%). Further mass loss observed above 260 ℃ indicates the decomposition of the coordination framework. The result indicates that the complex possesses excellent thermal stability, and a good thermal stability is a desired quality for photonic applications.

2.5 Photoluminescent properties

The photoluminescent behavior of complex 1 was investigated in the solid state at room temperature. In the excitation spectrum of complex 1, characteristic sharp peaks appearing at 361, 381, 393, 413, 463 and 532 nm correspond to the characteristic 7F0-5D4, 7F0-5L7, 7F0-5L6, 7F0-5D3, 7F0-5D2 and 7F1-5D1 electronic transitions of Eu(Ⅲ) ions, respectively(Fig.S4). The emission spectrum of the complex 1 was measured in the 550~750 nm range(λex=393 nm), and the emission typical of the Eu3+ ion is detected. Four sharp peaks appearing at 590, 611, 649 and 700 nm correspond to the characteristic f-f transitions of 5D0→7FJ(J=1~4) of Eu(Ⅲ) ions, which are in agreement with those reported for Eu(Ⅲ) complexes[55-60].

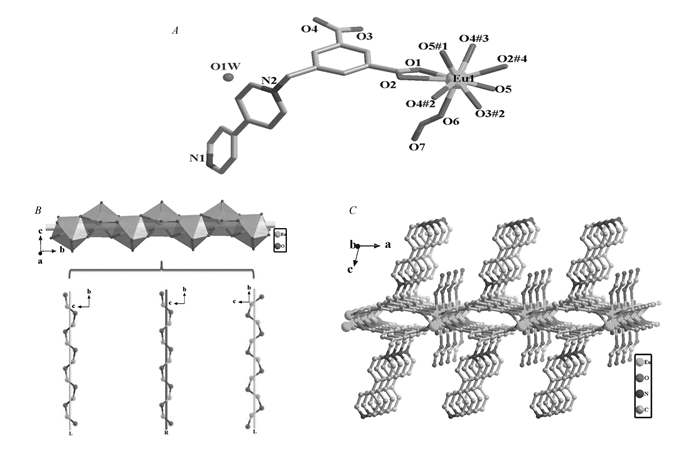

Complex 1 shows a fluorescence change accompanying the photochromic processes. It is noteworthy that the intensity of the fluorescence decreases gradually with the duration of irradiation until it comes to saturate, and the sample color becomes dark green. With the retrieve of the color to pale-yellow, the fluorescence intensity returns to its initial state. The reversibility of such fluorescence on/off behavior can be repeated several times without noticeable loss in its emission intensity(Fig. 6). The fluorescence quenching phenomenon with the irradiation can be explained by the overlap of the fluorescent emission spectra of the complex and UV-Vis diffuse reflectance spectra of colored sample. As shown in Fig.S5(Supporting Information), we can find the good overlap between the characteristic emission peaks of Eu3+ center and the broad absorption around 613 nm of the viologen radical, thus, the intramolecular energy transfer from the excited luminescence center to the colored state of the ligands leading to the observed results.

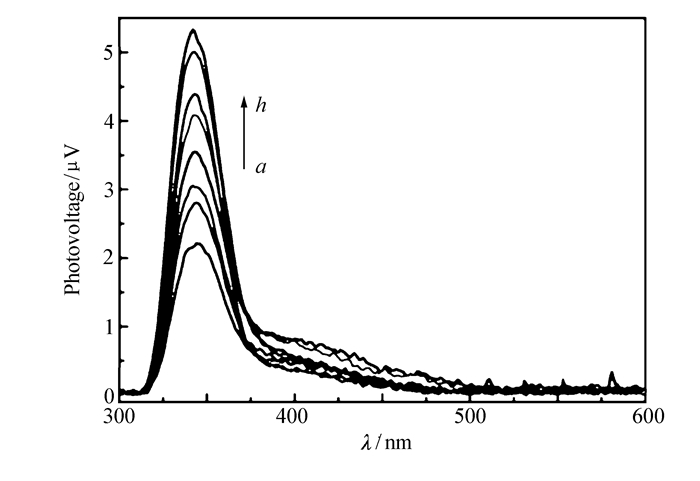

图6

The fluorescent emission spectra of complex 1 under different irradiation time. The inset shows the modulation of the fluorescence intensity at 618 nm due to alternating UV irradiation and heating treatment

Figure6.

The fluorescent emission spectra of complex 1 under different irradiation time. The inset shows the modulation of the fluorescence intensity at 618 nm due to alternating UV irradiation and heating treatment

图6

The fluorescent emission spectra of complex 1 under different irradiation time. The inset shows the modulation of the fluorescence intensity at 618 nm due to alternating UV irradiation and heating treatment

Figure6.

The fluorescent emission spectra of complex 1 under different irradiation time. The inset shows the modulation of the fluorescence intensity at 618 nm due to alternating UV irradiation and heating treatment

2.6 Second-order NLO properties

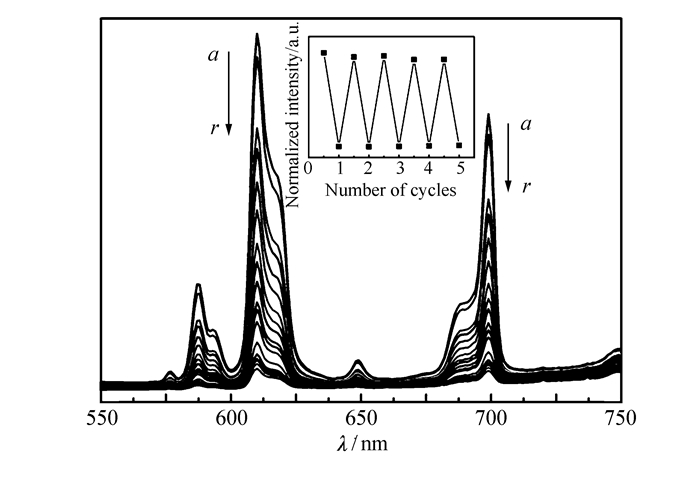

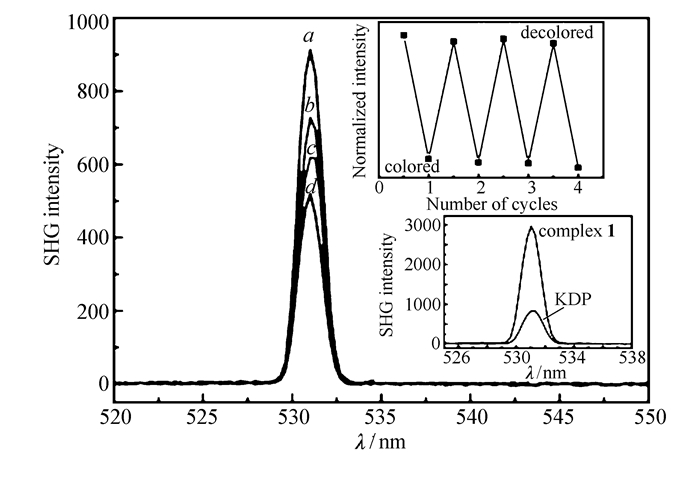

The research on the NLO materials has drawn increasingly attention due to their applications in many fields as telecommunications, optical storage, information processing and so on[61-63]. SHG is one of the most common NLO behaviours, it requires that the crystal structure belongs to the noncentrosymmetric space group[64]. On the other hand, a material possessing NLO properties that can be switched between two states triggered by external stimulus may have more practical applications. Given that the title compound 1 crystallizes in an acentric space group(P21), which belongs to a polar space group, its second-order NLO properties were investigated. Powder SHG measurements of complex 1 and the photocoloration products were performed by a pulsed laser at a wavelength of 1064 nm. Powder potassium dihydrogen phosphate(KDP) samples ground and sieved into different grain sizes were used as references. Interestingly, the intensity of the green light (frequency-doubled output: λ=532 nm) produced by the powder samples of complex 1 indicates that the original material is SHG-active with a value approximately 3.8 times of that produced by a KDP powder. This result demonstrates that complex 1 shows SHG effect which is a little stronger than that of KDP, making the original compound a potential candidate for new NLO materials.

While, the most striking feature of complex 1 is that, with the increasing of the photoirradiation time, the color of the product becomes dark and the SHG efficiency decreases, until it reaches a saturation, and the SHG intensity achieves about half of the initial value(as shown in Fig. 7). And with the de-coloration of the photocoloration sample, the SHG intensity can restore to the original level, suggesting the photoswitching of NLO properties. The photoswitching of SHG intensity can be cycled at least four times without detectable loss of efficiency(Fig. 7). It is well known that the non-centrosymmetric structure is an essential characteristic for the second-order NLO materials, which orginates from the inherent polarity of the structure[65]. Take the photophysical process into consideration, the drop of the SHG intensities with the irradiation time can be ascribed to the polarity decrease of the photocoloration products. In complex 1, the polarity comes from the asymmetric disposition of the different electron densities between the donor groups(dicarboxybenzyl and HCO2- unit) and the acceptor group(4, 4′-bipyridinium). As complex 1 is photosensitive and with the irridiation of the light, the photoinduced electron transfer weakens the different electron densities between the donor and acceptor groups, the asymmetric disposition of electron densities changes and thus obviously lowers the domain polarity. And the more electron transfer initiated by the photoirradiation, the smaller the value of the SHG response, thereby resulting in a decrease in the SHG intensity[66]. Thus, we can draw that the change of the electronic structure determines the NLO photoswitching.

图7

SHG intensity of complex 1 under 0(a), 5(b), 10(c) and 20(d) minute irradiation time. Insets:the normalized SHG intensity of the NLO switch process(top). The SHG intensity of the complex 1 and KDP as a reference in the same particle size(bottom)

Figure7.

SHG intensity of complex 1 under 0(a), 5(b), 10(c) and 20(d) minute irradiation time. Insets:the normalized SHG intensity of the NLO switch process(top). The SHG intensity of the complex 1 and KDP as a reference in the same particle size(bottom)

图7

SHG intensity of complex 1 under 0(a), 5(b), 10(c) and 20(d) minute irradiation time. Insets:the normalized SHG intensity of the NLO switch process(top). The SHG intensity of the complex 1 and KDP as a reference in the same particle size(bottom)

Figure7.

SHG intensity of complex 1 under 0(a), 5(b), 10(c) and 20(d) minute irradiation time. Insets:the normalized SHG intensity of the NLO switch process(top). The SHG intensity of the complex 1 and KDP as a reference in the same particle size(bottom)

2.7 Photovoltaic activity

Meanwhile, complex 1 exhibits interesting photovoltaic activity revealed using surface photovoltage(SPV) spectroscopy(SPS). As shown in Fig. 8, a broad SPV response ranging from 310 to 370 nm is observed, with a maximum at 342 nm. More interestingly, complex 1 shows a wonderful photomodulated SPV property, the intensity of the SPV response increases with the duration of irradiation. It is well known that photovoltaic effect is based on the photogeneration of excess carriers, followed by their spatial separation. Therefore, the photoinduced electron transfer in viologen-based complexes results in a spatial charge separation may be responsible for the photomodulated SPV property.

3 Conclusions

A chiral rare-earth metal-organic complex assembled by viologen-functionalized aromatic dicarboxylte ligand was synthesized, which displays a fast response to light irradiation. In addition, the unique chiral structure and the photoinduced electron transfer between the carboxylate donor and viologen acceptor trigger the turn/off of luminescence, photoswitchable second-order nonlinear optical activity, as well as photovoltaic activity. The results show that introducing viologen-based aromatic dicarboxylate derivative to metal-organic complex provides a unique platform to develop multi-functional photoresponse solid-state crystalline materials.

Supporting information [crystallographic data, IR, TGA and spectra of complex 1] is available free of charge on the of website Chinese Journal of Applied Chemistry(http://yyhx.ciac.jl.cn)

-

-

[1]

Ungur L, Lin S Y, Tang J. Single-Molecule Toroics in Ising-type Lanthanide Molecular Clusters[J]. Chem Soc Rev, 2014, 43(20): 6894-6905. doi: 10.1039/C4CS00095A

-

[2]

Bianchi A, Delgado-Pinar E, García-España E. Highlights of Metal Ion-based Photochemical Switches[J]. Coord Chem Rev, 2014, 260: 156-215. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.09.023

-

[3]

Irie M, Fukaminato T, Matsuda K. Photochromism of Diarylethene Molecules and Crystals:Memories, Switches, and Actuators[J]. Chem Rev, 2014, 114(24): 12174-12277. doi: 10.1021/cr500249p

-

[4]

Ratera I, Veciana J. Playing with Organic Radicals as Building Blocks for Functional Molecular Materials[J]. J Chem Soc Rev, 2012, 41: 303-349. doi: 10.1039/C1CS15165G

-

[5]

Zhang T, Lin W. Metal-Organic Frameworks for Artificial Photosynthesis and Photocatalysis[J]. Chem Soc Rev, 2014, 43: 5982-5993. doi: 10.1039/C4CS00103F

-

[6]

Guldi D M, Rahman G M A, Sgobba V. Multifunctional Molecular Carbon Materials from Fullerenes to Carbon Nanotubes[J]. Chem Soc Rev, 2006, 35(5): 471-487. doi: 10.1039/b511541h

-

[7]

Train C, Gruselle M, Verdaguer M. The Fruitful Introduction of Chirality and Control of Absolute Configurations in Molecular Magnets[J]. Chem Soc Rev, 2011, 40(6): 3297-3312. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15012j

-

[8]

Li P X, Wang M S, Cai L Z. Rare Electron-Transfer Photochromic and Thermochromic Difunctional Compounds[J]. J Mater Chem C, 2015, 3(2): 253-256. doi: 10.1039/C4TC01315H

-

[9]

Liao J Z, Zhang H L, Wang S S. Multifunctional Radical-Doped Polyoxometalate-Based Host-Guest Material:Photochromism and Photocatalytic Activity[J]. Inorg Chem, 2015, 54(9): 4345-4350. doi: 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.5b00041

-

[10]

Deng H, Doonan C J, Furukawa H. Multiple Functional Groups of Varying Ratios in Metal-Organic Frameworks[J]. Science, 2010, 327(5697): 846-850.

-

[11]

Ryder M R, Tan J C. Nanoporous Metal Organic Framework Materials for Smart Applications[J]. J Mater Sci Technol, 2014, 30(13): 1598-1612. doi: 10.1179/1743284714Y.0000000550

-

[12]

Wang M S, Xu G, Zhang Z J. Inorganic-Organic Hybrid Photochromic Materials[J]. Chem Commun, 2010, 46(3): 361-376. doi: 10.1039/B917890B

-

[13]

Pardo R, Zayat M, Levy D. Photochromic Organic-Inorganic Hybrid Materials[J]. Chem Soc Rev, 2011, 40(2): 672-687. doi: 10.1039/c0cs00065e

-

[14]

Yao Q X, Ju Z F, Jin X H. Novel Polythreaded Coordination Polymer:From an Armed-Polyrotaxane Sheet to a 3D Polypseudorotaxane Array, Photo-and Thermochromic Behaviors[J]. Inorg Chem, 2009, 48(4): 1266-1268. doi: 10.1021/ic8021672

-

[15]

Yao Q X, Pan L, Ju X H. Bipyridinium Array-Type Porous Polymer Displaying Hydrogen Storage, Charge-Transfer-Type Guest Inclusion, and Tunable Magnetic Properties[J]. Chem-Eur J, 2009, 15(44): 11890-11897. doi: 10.1002/chem.v15:44

-

[16]

Zhang C H, Sun L B, Zhang C Q. Novel Photo-and/or Thermochromic MOFs Derived from Bipyridinium Carboxylate Ligands[J]. Inorg Chem Front, 2016, 3(6): 814-820. doi: 10.1039/C6QI00013D

-

[17]

Aulakh D, Nicoletta A P, Varghese J R. The Structural Diversity and Properties of Nine New Viologen Based Zwitterionic Metal-Organic Frameworks[J]. CrystEngComm, 2016, 18(12): 2189-2202. doi: 10.1039/C6CE00284F

-

[18]

Deska M, Kozlowska J, Sliwa W. Rotaxanes and Pseudorotaxanes with Threads Containing Viologen Units[J]. ARKIVOC, 2013, : 66-100.

-

[19]

Higuchi M, Nakamura K, Horike S. Design of Flexible Lewis Acidic Sites in Porous Coordination Polymers by Using the Viologen Moiety[J]. Angew Chem, 2012, 124(33): 8494-8497. doi: 10.1002/ange.v124.33

-

[20]

Lin J B, Shimizu G K H. Pyridinium Linkers and Mixed Anions in Cationic Metal-Organic Frameworks[J]. Inorg Chem Front, 2014, 1(4): 302-305. doi: 10.1039/C3QI00065F

-

[21]

Aulakh D, Varghese J R, Wriedt M. A New Design Strategy to Access Zwitterionic Metal Organic Frameworks from Anionic Viologen Derivates[J]. Inorg Chem, 2015, 54(4): 1756-1764. doi: 10.1021/ic5026813

-

[22]

Sun J K, Zhang J. Functional Metal Bipyridinium Frameworks:Self-Assembly and Applications[J]. Dalton Trans, 2015, 44: 19041-19055. doi: 10.1039/C5DT03195H

-

[23]

Sun J K, Wang P, Yao Q X. Solvent-and Anion-Controlled Photochromism of Viologen-Based Metal-Organic Hybrid Materials[J]. J Mater Chem, 2012, 22(24): 12212-12219. doi: 10.1039/c2jm30558e

-

[24]

Sun J K, Cai L X, Chen Y J. Reversible Luminescence Switch in a Photochromic Metal Organic Framework[J]. Chem Commun, 2011, 47(24): 6870-6872. doi: 10.1039/c1cc11550b

-

[25]

Chen H, Zheng G, Li M. Photo-and Thermo-Activated Electron Transfer System Based on a Luminescent Europium Organic Framework with Spectral Response from UV to Visible Range[J]. Chem Commun, 2014, 50(88): 13544-13546. doi: 10.1039/C4CC05975A

-

[26]

Sun J K, Chen C, Cai L X. Mechanical Grinding of a Single-Crystalline Metal Mrganic Framework Triggered Emission with Tunable Violet-to-Orange Luminescence[J]. Chem Commun, 2014, 50(100): 15956-15959. doi: 10.1039/C4CC08316D

-

[27]

Jin X H, Sun J K, Cai L X. 2D Flexible Metal Organic Frameworks with[J]. Chem Commun, 2011, 47(9): 2667-2669. doi: 10.1039/c0cc04084c

-

[28]

Mitchell R H, Brkic Z, Sauro V A. A Photochromic, Electrochromic, Thermochromic Ru Complexed Benzannulene:An Organometallic Example of the Dimethyldihydropyrene-Metacyclophanediene Valence Isomerization[J]. J Am Chem Soc, 2003, 125(25): 7581-7585. doi: 10.1021/ja034807d

-

[29]

Li M H, Keller P. Stimuli-Responsive Polymer Vesicles[J]. Soft Matter, 2009, 5: 927-937. doi: 10.1039/b815725a

-

[30]

Jaffe A, Lin Y, Mao W L. Pressure-Induced Conductivity and Yellow-to-Black Piezochromism in a Layered Cu-Cl Hybrid Perovskite[J]. J Am Chem Soc, 2015, 137(4): 1673-1678. doi: 10.1021/ja512396m

-

[31]

Wu J H, Liou G S. High-Performance Electrofluorochromic Devices Based on Electrochromism and Photoluminescence-Active Novel Poly(4-Cyanotriphenylamine)[J]. Adv Funct Mater, 2014, 24(41): 6422-6429. doi: 10.1002/adfm.v24.41

-

[32]

Yao J, Hashimoto K, Fujishima A. Photochromism Induced in an Electrolytically Pretreated Mo03 Thin Film by Visible Light[J]. Nature, 1992, 355: 624-626. doi: 10.1038/355624a0

-

[33]

Irie M. Diarylethenes for Memories and Switches[J]. Chem Rev, 2000, 100(5): 1685-1716. doi: 10.1021/cr980069d

-

[34]

de Jong J J D, Lucas L N, Kellogg R M. Astronomers Attempt to Stay in the Big League[J]. Science, 2004, 304(5669): 378-380. doi: 10.1126/science.304.5669.378

-

[35]

Li H Y, Xu H, Zang S Q. A Viologen-functionalized Chiral Eu-MOF as a Platform for Multifunctional Switchable Material[J]. Chem Commun, 2016, 52(3): 525-528. doi: 10.1039/C5CC08168H

-

[36]

Li H Y, Wei Y L, Dong X Y. Novel Tb-MOF Embedded with Viologen Species for Multi-Photofunctionality:Photochromism, Photomodulated Fluorescence, and Luminescent pH Sensing[J]. Chem Mater, 2015, 27(4): 1327-1331. doi: 10.1021/cm504350q

-

[37]

Lvaro Á, Ferrer M, Fornés V B. A Periodic Mesoporous Organosilica Containing Electron Acceptor Viologen Units[J]. Chem Commun, 2001, 24: 2546-2547.

-

[38]

Park Y S, Um S Y, Yoon K B. Charge-Transfer Interaction of Methyl Viologen with Zeolite Framework and Dramatic Blue Shift of Methyl Viologen-Arene Charge-Transfer Band upon Increasing the Size of Alkali Metal Cation[J]. J Am Chem Soc, 1999, 121(13): 3193-3200. doi: 10.1021/ja980912p

-

[39]

Berthet J J, Micheau C, Metelitsa A. Multistep Thermal Relaxation of Photoisomers in Polyphotochromic Molecules[J]. J Phys Chem A, 2004, 108(50): 10934-10940. doi: 10.1021/jp046864e

-

[40]

Sheldrick G M. Acta Crystallogr, Sect. A:Fundam Crystallogr[M]. 1990, 46:457.

-

[41]

Sheldrick G M. SHELXS-97, Program for Solution of Crystal Structures[M]. University of G ttingen, Germany, 1997.

-

[42]

Sheldrick G M. SHELXL-97, Program for Refinement of Crystal Structures[M]. University of G ttingen, Germany, 1997.

-

[43]

Tan Y, Fu Z Y, Zeng Y. Highly Stable Photochromic Crystalline Material Based on a Close-Packed Layered Metal-Viologen Coordination Polymer[J]. J Mater Chem, 2012, 22(34): 17452-17455. doi: 10.1039/c2jm34341j

-

[44]

Toma O, Mercier N, Allain M. Photo-and Thermochromic and Adsorption Properties of Porous Coordination Polymers Based on Bipyridinium Carboxylate Ligands[J]. Inorg Chem, 2015, 54(18): 8923-8930. doi: 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.5b00975

-

[45]

Matsunaga Y, Goto K, Kubono K. Photoinduced Color Change and Photomechanical Effect of Naphthalene Diimides Bearing Alkylamine Moieties in the Solid State[J]. Chem Eur J, 2014, 20(24): 7309-7316. doi: 10.1002/chem.201304849

-

[46]

Xu G, Guo G C, Wang M S. Photochromism of a Methyl Viologen Bismuth(Ⅲ) Chloride:Structural Variation before and after UV Irradiation[J]. Angew Chem Int Ed, 2007, 46(18): 3249-3251. doi: 10.1002/(ISSN)1521-3773

-

[47]

Xu G, Guo G C, Guo J S. Photochromic Inorganic-Organic Hybrid:A New Approach for Switchable Photoluminescence in the Solid State and Partial Photochromic Phenomenon[J]. Dalton Trans, 2010, 39(37): 8688-8692. doi: 10.1039/c0dt00471e

-

[48]

Lin R G, Xu G, Wang M S. Improved Photochromic Properties on Viologen-Based Inorganic-Organic Hybrids by Using π-Conjugated Substituents as Electron Donors and Stabilizers[J]. Inorg Chem, 2013, 52(3): 1199-1205. doi: 10.1021/ic301181b

-

[49]

Sun J K, Ji M, Chen C. A Charge-Polarized Porous Metal-Organic Framework for Gas Chromatographic Separation of Alcohols from Water[J]. Chem Commun, 2013, 49(16): 1624-1626. doi: 10.1039/c3cc38260e

-

[50]

Hutchison G R, Ratner M A, Marks T J. Intermolecular Charge Transfer Between Heterocyclic Oligomers. Effects of Heteroatom and Molecular Packing on Hopping Transport in Organic Semiconductors[J]. J Am Chem Soc, 2005, 127(48): 16866-16881. doi: 10.1021/ja0533996

-

[51]

Jhang P C, Chuang N T, Wang S L. Layered Zinc Phosphates with Photoluminescence and Photochromism:Chemistry in Deep Eutectic Solvents[J]. Angew Chem Int Ed, 2010, 49(25): 4200-4204. doi: 10.1002/anie.v49:25

-

[52]

Lin R G, Xu G, Lu G. Photochromic Hybrid Containing In Situ-Generated Benzyl Viologen and Novel Trinuclear[Bi3Cl14]5-:Improved Photoresponsive Behavior by the π…π[JG)] Interactions and Size Effect of Inorganic Oligomer[J]. Inorg Chem, 2014, 53(11): 5538-5545. doi: 10.1021/ic5002144

-

[53]

Yoshikawa H, Nishikiori S I, Watanabe T. Polycyano-Polycadmate Host Clathrates Including a Methylviologen Dication. Syntheses, Crystal Structures and Photo-Induced Reduction of Methylviologen Dication[J]. J Chem Soc Dalton Trans, 2002, 43(9): 1907-1917.

-

[54]

Jin X H, Sun J K, Xu X M. Conformational and Photosensitive Adjustment of the 4, 4'-Bipyridinium in Mn(Ⅱ) Coordination Complexes[J]. Chem Commun, 2010, 46(26): 4695-4697. doi: 10.1039/c0cc00135j

-

[55]

Sava D F, Rohwer L E S, Rodriguez M A. Intrinsic Broad-Band White-Light Emission by a Tuned, Corrugated Metal-Organic Framework[J]. J Am Chem Soc, 2012, 134(9): 3983-3986. doi: 10.1021/ja211230p

-

[56]

Xu H, Cao C S, Zhao B. A Water-Stable Lanthanide-Organic Framework as a Recyclable Luminescent Probe for Detecting Pollutant Phosphorus Anions[J]. Chem Commun, 2015, 51: 10280-10283. doi: 10.1039/C5CC02596F

-

[57]

Xu H, Cao C S, Kang X M. Lanthanide-Based Metal Organic Frameworks as Luminescent Probes[J]. Dalton Trans, 2016, 45(45): 18003-18017. doi: 10.1039/C6DT02213H

-

[58]

Xu H, Zhai B, Cao C S. A Bifunctional Europium-Organic Framework with Chemical Fixation of CO2 and Luminescent Detection of Al3+[J]. Inorg Chem, 2016, 55(19): 9671-9676. doi: 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.6b01407

-

[59]

Li H N, Li H Y, Li L K. Syntheses, Structures, and Photoluminescent Properties of Lanthanide Coordination Polymers Based on a Zwitterionic Aromatic Polycarboxylate Ligand[J]. Cryst Growth Des, 2015, 15(9): 4331-4340. doi: 10.1021/acs.cgd.5b00625

-

[60]

Ma M L, Ji C, Zang S Q. Syntheses, Structures, Tunable Emission and White Light Emitting Eu3+ and Tb3+ Doped Lanthanide Metal Organic Framework Materials[J]. Dalton Trans, 2013, 42(29): 10579-10586. doi: 10.1039/c3dt50315a

-

[61]

Jain K, Pratt G W. Optical Transistor[J]. Appl Phys Lett, 1976, 28: 719-721. doi: 10.1063/1.88627

-

[62]

Zyss J, Chemla D S. Nonlinear Optical Properties of Organic Molecules and Crystals[M]. New York:Academic Press, 1989, 1:23-191.

-

[63]

Keszler D A. Synthesis, Crystal Chemistry, and Optical Properties of Metal Borates[J]. Curr Opin Solid State Mater Sci, 1999, 4(2): 155-162. doi: 10.1016/S1359-0286(99)00011-X

-

[64]

Nye J F. Physical Properties of Crystals:Their Representation by Tensors and Matrices[M]. Clarendon, Oxford, 1985.

-

[65]

Bella S D. Second-Order Nonlinear Optical Properties of Transition Metal Complexes[J]. Chem Soc Rev, 2001, 30(6): 355-366. doi: 10.1039/b100820j

-

[66]

Li P X, Wang M S, Zhang M J. Electron-Transfer Photochromism to Switch Bulk Second-Order Nonlinear Optical Properties with High Contrast[J]. Angew Chem Int Ed, 2014, 53(43): 11529-11531. doi: 10.1002/anie.201406554

-

[1]

-

Figure 1 (A)The asymmetric unit of complex 1. Symmetry codes:#1.-x+2, y+1/2, -z; #2.-x+2, y-1/2, -z; #3.-x+1, y-1/2, -z; #4.x+1, y, z; #5.x-1, y, z; #6.-x+1, y+1/2, -z.(All hydrogen atoms and solvent molecules are omitted for clarity). (B)View of the three co-axial helical chains of the 1D rod-like chain in 1. (C)The two-dimensional layer structure viewed from b direction with the pyridinium rings hanging up and down the plane

Figure 6 The fluorescent emission spectra of complex 1 under different irradiation time. The inset shows the modulation of the fluorescence intensity at 618 nm due to alternating UV irradiation and heating treatment

Irradiation time (a~r)/s:0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 90, 120, 180, 240, 300, 420, 600, 900, 1200

-

扫一扫看文章

扫一扫看文章

计量

- PDF下载量: 6

- 文章访问数: 915

- HTML全文浏览量: 159

下载:

下载:

下载:

下载: