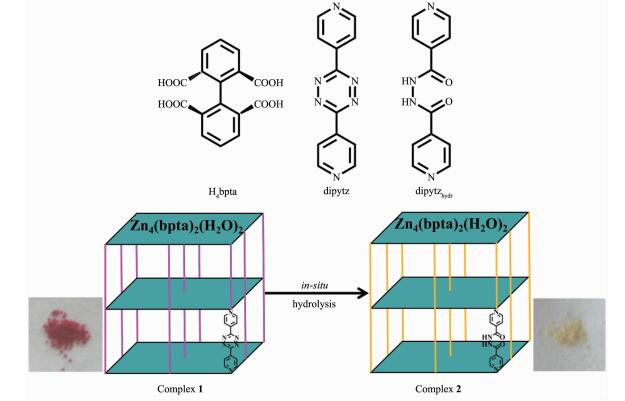

图Scheme 1

Structure of ligands, synthesis process of complexes and the corresponding images of the products

Scheme1.

Structure of ligands, synthesis process of complexes and the corresponding images of the products

图Scheme 1

Structure of ligands, synthesis process of complexes and the corresponding images of the products

Scheme1.

Structure of ligands, synthesis process of complexes and the corresponding images of the products

通过有机配体中四嗪基团的原位水解提高金属有机框架的CO2吸附性能

English

Enhanced CO2 Sorption Performance of Metal-Organic Frameworks by in-Situ Hydrolysis of Tetrazine Moiety in the Ligand

-

Key words:

- metal-organic frameworks

- / tetrazine

- / post-synthesis

- / property modulation

- / CO2 sorption

-

0 Introduction

With the rapid development of modern industry, CO2 release from burning fossil fuels has been a global environmental issue[1] and it calls for much efforts on the capture and separation of CO2[2-4]. Among the various strategies for CO2 capture, physical adsorption with porous materials is considered to be one of the effective methods[5], and the development of porous materials with high CO2 adsorption capacity has attracted much attention in recent years[6-7].

Due to the adjustable pore size, high porosity and large surface area, metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) has become a promising candidate for gas adsorption and separation[8-15]. The strategies for improving CO2 adsorption capacity and selectivity of MOFs include the incorporation of unsaturated metal cation centers, metal doping and chemical functionalization. Among them, chemical functionalization has been proved to be simple and efficient due to the diversity of functionalized groups[16-17].

Among numerous organic ligands, tetrazine derivative ligands are widely used in function-oriented construction of MOFs[18-24], and the tetrazine moiety can be hydrolyzed to form polar acyl hydrazine groups[25-26]. This feature can help to enhance the affinity toward CO2 and promote the adsorption and separation performance of the corresponding MOFs. However, in contrast to the rigid aromatic moiety of the parental tetrazine moiety, the flexible backbone of the acyl hydrazine moiety may affect the assembly of porous MOFs with desirable structure, which could limit the application of direct synthesis method. On the other hand, as an alternative method, the post-synthesis in-situ hydrolysis of tetrazine moiety into acyl hydrazine requires high stability and strong resistance toward moisture, which is difficult to meet for most MOFs. Therefore, it is our interest to overcome the disadvantage and achieve the targeted introduction of acyl hydrazine moiety into MOFs from hydrolysis of tetrazine for enhanced CO2 sorption and separation.

Based on our previous studies, the "pillar-layer" strategy, where the "layers" are composed of 1, 1′-biphenyl-2, 2′, 6, 6′-tetracarboxylic acid (H4bpta) and Zn2+ ions and the bipyridine ligands serve as "pillar", has been proved to be effective for the targeted construction of porous framework with distinct sorption behaviors[27-28]. In this system, the utilization of pillar ligand di-3, 6-(4-pyridyl)-1, 2, 4, 5-tetrazine (dipytz) can result in desired "pillar-layer" structure [Zn4(bpta)2(dipytz)2(H2O)2]·4DMF·H2O and can tune the pore geometry[28], as is estimated from the powder X-ray diffraction patterns. Considering the feature of tetrazine moieties, [Zn4(bpta)2(dipytz)2(H2O)2] was chosen and the post-synthesis in-situ hydrolysis modification is achieved. Herein, we report the structure of [Zn4(bpta)2(dipytz)2(H2O)2]·4DMF·H2O (1) and the construction of [Zn4(bpta)2(dipytzhydr)2(H2O)2]·solvent (2) (dipytzhydr=1, 2-diisonicotinoylhydrazine) from complex 1 through post-synthesis in-situ hydrolysis modification (Scheme 1). Due to the moisture stability of the framework of complex 1, the porous "pillar-layer" framework is well retained after the modification process, and the resulted complex 2 reveals enhanced affinity toward CO2 compared to that of complex 1. The presence of polar acyl hydrazine moiety in complex 2 results in better CO2/CH4 selectivity as expected.

图Scheme 1

Structure of ligands, synthesis process of complexes and the corresponding images of the products

Scheme1.

Structure of ligands, synthesis process of complexes and the corresponding images of the products

图Scheme 1

Structure of ligands, synthesis process of complexes and the corresponding images of the products

Scheme1.

Structure of ligands, synthesis process of complexes and the corresponding images of the products

1 Experimental

1.1 Materials and methods

All solvents and chemicals for synthesis were obtained commercially and used without further purification. H4bpta and dipytz were synthesized according to the reported methods[29-30]. The powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) patterns were recorded by a Rigaku Miniflex 600 diffractometer at 40 kV and 15 mA with a Cu Kα radiation (λ=0.154 18 nm) and a graphite monochromator in the range of 3°~50°. Ther-mogravimetric analysis (TGA) was performed with a Rigaku standard TG-DTA analyzer with heating rate of 10 ℃·min-1 between room temperature and 800 ℃ in air; empty Al2O3 crucible was used as reference. IR spectra were carried out on a Tensor 37 (Bruker, German) FT-IR spectrometer in the range of 400~4 000 cm-1 using KBr pellets. Elemental Analysis (C, H and N) were performed on a Vario EL cube analyzer.

1.2 Synthesis of the complexes

[Zn4(bpta)2(dipytz)2(H2O)2]·4DMF·H2O (1). Zn(NO3)2·6H2O (0.1 mmol), H4bpta (0.05 mmol) and dipytz (0.05 mmol) were added to a DMF/ethanol mixture (10 mL, VDMF/VEtOH=1), sealed in a capped vial and ultra-sonicated for 30 min. Then the vial was kept at 80 ℃ for 24 h. Pale red bulk crystals were collected by filtration, then washed with DMF, and dried in air (Yield: 70% based on H4bpta). FT-IR (KBr pellets, cm-1): 3 855 w, 3 742 m, 3 423 s, 2 362 m, 2 322 m, 1 835 w, 1 601 s, 1 550 s, 1 459 m, 1 386 s, 1 220 w, 1 159 w, 1 063 w, 1 025 w, 924 w, 839 m, 777 m, 715 m, 601 m, 534 w, 454 w. Anal. Calcd. for C68H62N16O23Zn4(%): C, 47.13; H, 3.61; N, 12.93. Found(%): C, 47.31; H, 3.30; N, 12.90.

[Zn4(bpta)2(dipytzhydr)2(H2O)2]·solvent (2). Complex 2 was produced by heating complex 1 in water at 80 ℃ for 12 h. Yellow crystalline powder were collected by filtration, washed with H2O and dried in air (Yield: 98%, based on complex 1). FT-IR (KBr pellets, cm-1): 3 925 w, 3 897 w, 3 862 w, 3 743 w, 3 423 s, 2 362 m, 2 333 m, 1 917 w, 1 868 w, 1 837 w, 1 677 m, 1 611 s, 1 551s, 1 458 m, 1 372 s, 1 294 m, 1 222 w, 1 154 w, 1 102 w, 1 067 w, 1 028 w, 930 w, 835 m, 778 m, 713 m, 666 m, 589 w, 539 w, 451 w, 422 w.

1.3 Crystal structure determination

Single-crystal X-ray diffraction measurement was conducted at BL16B1 beamline at Shanghai Synchro-tron Radiation Facility (SSRF) at 113 K. The deter-minations of unit cell parameters and data collections were performed with Mo Kα radiation (λ=0.071 073 nm), and unit cell dimensions were obtained with least-squares refinements. The structure of 1 was solved by direct methods using the SHELXS of the SHELXTL and refined by SHELXL[31]. Zinc atoms in 1 were located from the E maps, and other non-hydrogen atoms were located in successive difference Fourier synthesis and refined anisotropically. The hydrogen atoms were added theoretically, riding on the concerned atoms, and refined with fixed thermal factor. The final refinement was performed by full-matrix least-squares methods with anisotropic thermal parameters for non-hydrogen atoms on F2. The solvent molecules in 1 were disordered and could not be modeled properly, so the contribution of disordered solvent molecules were removed by SQUEEZE in PLATON[32] and the results were appended in the CIF file. Detailed crystallographic data were summarized in Table S1, and the selected bond lengths and angles are given in Table S2 and S3(Supporting Information).

CCDC: 1567303, 1.

1.4 Gas sorption measurements

Gas sorption measurements were performed with an ASAP 2020 M gas adsorption analyzer. UHP-grade gases were used in measurements. The N2 sorption isotherm measurements were proceeded at 77 K. The CO2 and CH4 sorption isotherm measurements were carried out at 273 and 298 K, respectively.

Before measurements, the samples were soaked in anhydrous methanol for 3 days to exchange solvent molecules in the channels and then filtrated and dried at room temperature. Activation of the methanol-exchanged samples was performed under high vacuum (less than 1.33 mPa) at 50 ℃ overnight. About 100 mg of the desolvated samples were used for gas sorption measurements.

2 Results and discussion

2.1 Synthesis of complexes

Complex 1 was synthesized based on the reported method[28], while single-crystal suitable for X-ray diffraction analysis were obtained. Therefore, the structure of complex 1 was determined straightfor-wardly.

To achieve the post-synthesis in-situ hydrolysis modification of complex 1, various methods have been tried, and it was found that direct heating of complex 1 in water could be a straightforward way, proved by the fading of the characteristic red color of tetrazine moiety of the sample originated from the opening of rings. It should be noted that the crystallinity of the sample is well retained after the hydrolysis. This should be attributed to the relatively high moisture stability of the Zn4(bpta)2(H2O)2 layer structure and the Zn-N coor-dination bonds that could survive the hydrolysis reaction conditions. As a result, complex 2 was obtained as expected. Though no suitable crystal for single-crystal X-ray diffraction analysis was obtained for complex 2, the high crystallinity just benefits its further characterization and properties investigations.

2.2 Structure determination

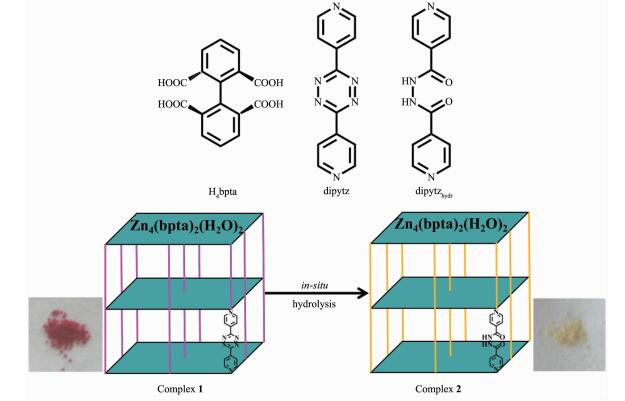

Single-crystal X-ray diffraction analysis reveals that complex 1 crystallizes in the monoclinic space group C2/c. As shown in Fig. 1a, there are two types of crystallographically independent Zn2+ ions, one bpta4- ligand, one dipytz ligand and one H2O molecule in the asymmetric unit of 1. The Zn1 center is four-coordinated by three carboxylate oxygen atoms from three different bpta4- ligands and one nitrogen atom from one dipytz ligand to form a tetrahedral geometry. The Zn2 center adopts a six-coordinated distorted octahedral geometry, completed by four O atoms of three carboxylate groups from two bpta4- ligands, one O atom from the terminal H2O, and one N atom from one dipytz ligand. In the direction of the a axis, two-dimensional (2D) layers are constructed by bpta4- ligands connecting with Zn2+ ions. Each bpta4- coord-inates to five Zn2+ centers through four carboxylate groups by mondentate or bidentate coordination modes (Fig. 1b). Furthermore, dipytz ligands serve as "pillar" and connect adjacent layers to form three-dimensional (3D) "pillar-layered" frameworks, which contain chan-nels alone the b and c axis (Fig. 1c and 1d). The channels are filled with solvent molecules. PLATON analysis showed that the accessible volume of 1 is 38.9% of the crystal volume (3.138 9 nm3 out of 8.076 0 nm3 for unit cell volumes) after removal solvent molecules in frameworks. It should be noted that the cell parameters determined herein consist well with that obtained from PXRD patterns[28], and the incre-ased porosity of complex 1 compared with other complexes based on shorter pillar ligands suggests that the application of longer ligand could benefit the formation of porous framework.

图1

Crystal structure of 1: (a) Coordination environment of Zn2+ ions; (b) 2D layer assembled by Zn2+ ions and bpta4- ligands viewing along the a direction; (c) Channels along b direction; (d) Channels along c direction

Figure1.

Crystal structure of 1: (a) Coordination environment of Zn2+ ions; (b) 2D layer assembled by Zn2+ ions and bpta4- ligands viewing along the a direction; (c) Channels along b direction; (d) Channels along c direction

图1

Crystal structure of 1: (a) Coordination environment of Zn2+ ions; (b) 2D layer assembled by Zn2+ ions and bpta4- ligands viewing along the a direction; (c) Channels along b direction; (d) Channels along c direction

Figure1.

Crystal structure of 1: (a) Coordination environment of Zn2+ ions; (b) 2D layer assembled by Zn2+ ions and bpta4- ligands viewing along the a direction; (c) Channels along b direction; (d) Channels along c direction

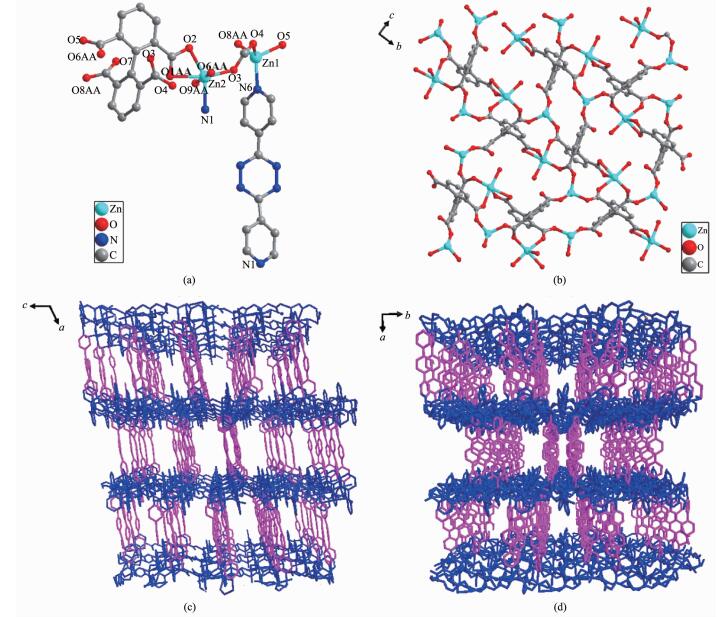

As no suitable crystal of complex 2 for single-crystal X-ray diffraction measurement was obtained, the structure as well as the component of the crystalline product was determined by comprehensive characterization by FT-IR and PXRD. As mentioned in the synthesis part, the complete fading of the red color of complex 1 in the hydrolysis reaction can be ascribed to the ring opening of tetrazine moiety in the dipytz ligand and the corresponding formation of acyl hydrazine group. Beside the change of color, this reaction can also be proved by the FT-IR spectra: two new characteristic absorption peaks appear in the location of 1 677 and 1 294 cm-1 in the spectrum of complex 2 compared with that of complex 1 (Fig. 2), which should be attributed to the presence of carbonyl and imino groups in the sample from the hydrolysis of tetrazine. Furthermore, the elemental analysis of complex 2 after removal of solvent at 150 ℃ also confirms the result. The experimental values (C, 47.47; H, 2.93; N, 7.58) matches the theoretical values (calculated as C56H35N8Zn4O21.5, C, 47.18; H, 2.47; N, 7.86) well, which directly proves the occurrence of the hydrolysis reaction. All these results suggest the complete hydrolysis of dipytz and the formation of dipytzhydr during the post-synthesis reaction. On the other hand, the similar PXRD pattern indicates that complex 2 possesses the similar "pillar-layered" structure of 1 (Fig. 3) with the dipytzhydr ligand serve as pillars. Then the framework of complex 2 could be assigned as Zn4(bpta)2(dipytzhydr)2(H2O)2 according to the component and structure of complex 1.

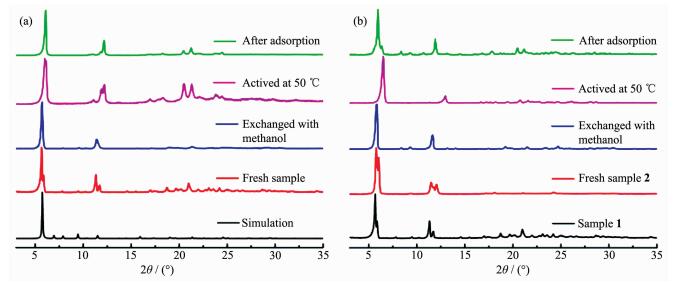

2.3 Phase purity and stability investigations

PXRD was performed to confirm the phase purity and stability of complexes 1 and 2 after solvent exchange and degas process, as shown in Fig. 3. For 1, the pattern of as-synthesized sample matches well with the simulated pattern from single-crystal data, suggesting the phase purity of the bulk sample. While for complex 2, the PXRD patterns of the as-synthesized sample is nearly the same as that of complex 1, indicating the structural similarity of these two complexes. Furthermore, solvent-exchanged and activated samples of both complexes are still crystalline, indicating the good stability of complexes. The shift of peaks and appearance of new peaks should be attributed to the distortion of the crystal lattice in response to removal of guest molecules, which is commonly observed in many MOFs[28]. Interestingly, the peak displacement of complex 2 after degassed at 50 ℃ is more significant than that of complex 1. This phenomenon should be attributed to the more flexible backbone of dipytzhydr compared with that of dipytz. The hydrolysis reaction of rigid tetrazine ring result in acyl hydrazine group with non-rigid backbone. Accordingly, the framework of complex 2 should be more flexible and more responsive to the removal of guest molecules. It should be noted that when the samples of complexes 1 and 2 were exposed to air after gas adsorption experiments, the patterns could restore well. These results suggest the structure transformation is reversible upon the removal and recovery of guest molecules, which should be originated from the flexibility of the pillar ligands and the framework.

TGA experiments reflect the thermal stability of materials (Fig.S1 and S2, Supporting Information). The TG curve of complex 1 shows weight loss of 12.1% from 30 to 140 ℃ corresponding to the loss of solvent molecules. A sustained weight loss followed from 140 to 210 ℃ responses to hydrolysis of dipytz with ring opening. However, after the sample was soaked in methanol for 3 days, hydrolysis is prevented. What′s more, the loss of coordinated H2O occurs at 163 ℃ and the framework could be stable up to 340 ℃.

The TG curve of complex 2 shows 20% weight loss before 100 ℃, which should be assigned to the removal of solvent molecules. Then it reveals a weight loss of 3% in the temperature range of 100~177 ℃, which responses to the weight of coordinated H2O molecules. Also, the activated sample 2 shows high thermal stability up to 340 ℃, indicating the high thermal stability of these "pillar-layered" MOFs.

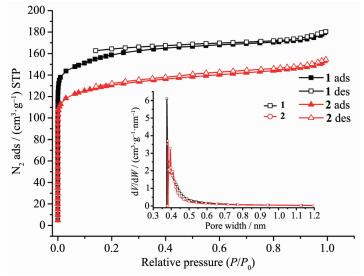

2.4 Adsorption studies

Nitrogen gas adsorption experiments at 77 K were performed to investigate the porosity of complexes 1 and 2 (Fig. 4). All samples were activated at 50 ℃ before the measurements. As shown in Fig. 4, both the N2 sorption isotherms of the activated samples of 1 and 2 illustrate fully reversible type Ⅰ isotherms, which indicates the microporous structure of the complexes. The saturation uptake is 180.6 cm3·g-1 for 1 and 155.2 cm3·g-1 for 2, respectively. The total microporous volume is calculated to be 0.28 cm3·g-1 for 1 and 0.24 cm3·g-1 for 2 (calculated by Horvath-Kawazoe model), while the pore size distributions are almost identical (Fig. 4 inset). These sorption isotherms were analyzed by the methods of Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) and Langmuir. The apparent BET and Langmuir surface areas are 514 and 712 m2·g-1 for 1 and 420 and 586 m2·g-1 for 2, respectively. Considering the conclusions from PXRD discussions, the reduced surface area and pore volume of complex 2 compared to those of 1 should be attributed to the shrink of flexible framework in response to the removal of guest molecules.

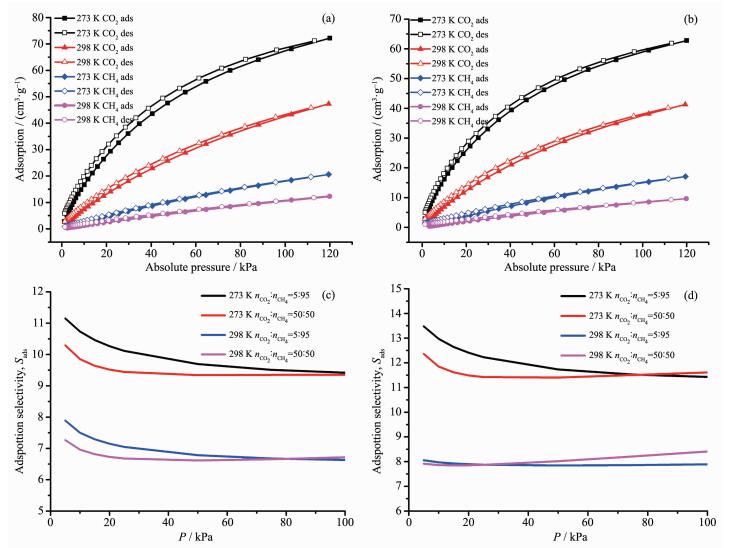

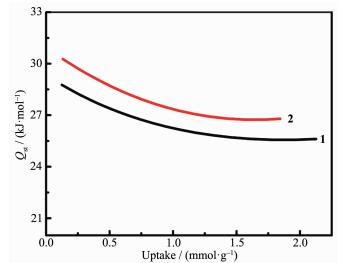

On the basis of previous research, the presence of carboxamide group in MOFs may benefit its selectivity adsorption performance toward CO2 due to the enhanced gas-framework affinity. Therefore, CO2 adsorption isotherms of 1 and 2 were recorded at 273 and 298 K, respectively, to evaluate the effect of post-synthesis modification on CO2 sorption and separation (Fig. 5a and 5b). The maximum CO2 uptake of 1 reaches to 72.2 cm3·g-1 at 273 K, 120 kPa and 47.3 cm3·g-1 at 298 K, 120 kPa. For 2, the CO2 maximum adsorption amounts are 62.8 cm3·g-1 at 273 K, 120 kPa and 41.3 cm3·g-1 at 298 K, 120 kPa. The differences between the CO2 uptakes of complexes 1 and 2 under the same conditions fit their differences in pore volume determined from N2 sorption well. To further evaluate the interaction between the adsorbed CO2 molecules and the frameworks, the CO2 adsorption enthalpies (Qst) of 1 and 2 are calculated using the Virial equation by fitting adsorption isotherms at 273 and 298 K (Fig. 6). The CO2 Qst value of 1 is 28.8 kJ·mol-1 at zero loading, while the initial Qst value of 2 increases to 30.3 kJ·mol-1, which indicates a relatively stronger interaction between CO2 and the framework of complex 2. It should be noted that Qst value of complex 2 surpass that of complex 1 in the whole range of loading. This should be attributed to the readily accessible polar acyl hydrazine sites on the pore surface defined by the backbone of dipytzhydr pillar, which could be accessed in the whole gas sorption procedure due to the limited pore dimension. These results prove that the post-synthesis in-situ hydrolysis of tetrazine could be an effective method for the targeted modification of MOFs toward CO2 sorption.

In addition to the evaluation of Qst, the ideal adsorbed solution theory (IAST) calculation was also employed to further evaluate the effect of modification on selective CO2 adsorption over CH4. The binary CO2/CH4 mixtures with molar ratio of 5:95 and 50:50 were selected as model system. To establish the relationship between the CH4 uptake and pressure for calculation, the CH4 adsorption isotherm were also measured at 273 and 298 K. The maximum CH4 uptakes of 1 are 20.6 cm3·g-1 at 273 K and 12.3 cm3·g-1 at 298 K. For 2, the values are 17.1 cm3·g-1 at 273 K and 9.7 cm3·g-1 at 298 K, respectively. Then, the single-component isotherms of CO2 and CH4 at 273 and 298 K were fitted with Langmuir-Freundlich equation (Fig.S3, Supporting Information), and the fitting parameters (Table S4) are used for the IAST calculations.

As shown in Fig. 5c, the calculated selectivity of CO2 over CH4 for complex 1 are 11.1 (nCO2:nCH4=5:95), 10.3 (nCO2:nCH4=50:50) at 273 K and 7.9 (5:95), 7.3 (50:50) at 298 K. While the calculated CO2/CH4 selectivity of complex 2 are 13.5 (5:95), 12.4 (50:50) at 273 K and 8.1 (5:95), 7.9 (50:50) at 298 K as shown in Fig. 5d. Obviously, the CO2/CH4 selectivity of complex 2 are enhanced compared with that of complex 1, which in line with the results calculated from Qst. For complexes 1 and 2, the relatively higher selectivity occurs at lower pressure and lower temperature, which benefiting from the improved CO2 storage capacities and enhanced CO2 binding affinity of frameworks.

3 Conclusions

In summary, the post-synthesis in-situ hydrolysis of tetrazine moiety in MOFs was investigated for improving CO2 sorption performance. With this method, [Zn4(bpta)2(dipytz)2(H2O)2]·4DMF·H2O (1) was succe-ssfully modified into [Zn4(bpta)2(dipytzhydr)2(H2O)2]·solvent (2) with polar acyl hydrazine groups, of which the "pillar-layer" framework structure is well retained. Complex 2 represents enhanced CO2-framework affinity and CO2/CH4 selectivity compared with that of complex 1, as expected. The achievement in this work provides a valuable strategy for the targeted construction and modification of MOFs toward CO2 sorption applications.

Supporting information is available at http://www.wjhxxb.cn

-

-

[1]

D'Alessandro D M, Smit B, Long J R. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 2010,49:6058-6082 doi: 10.1002/anie.201000431

-

[2]

Jacobson M Z. Energy Environ. Sci., 2009,2:148-155 doi: 10.1039/B809990C

-

[3]

Sumida K, Rogow D L, Mason J A, et al. Chem. Rev., 2012, 112:724-781 doi: 10.1021/cr2003272

-

[4]

Nugent P, Belmabkhout Y, Burd S D, et al. Nature, 2013, 495:80-84 doi: 10.1038/nature11893

-

[5]

Haszeldine R S. Science, 2009,325:1647-1652 doi: 10.1126/science.1172246

-

[6]

Christopher W J, Edward J M. ChemSusChem, 2010,3:863-864 doi: 10.1002/cssc.201000235

-

[7]

Rubin E S, John H, Marks A, et al. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci., 2012,38:630-671 doi: 10.1016/j.pecs.2012.03.003

-

[8]

Wang H, Xu J, Bu X H, et al. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 2015, 54:5966-5699 doi: 10.1002/anie.201500468

-

[9]

Tian D, Chen Q, Bu X H, et al. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 2014, 53:837-849 doi: 10.1002/anie.201307681

-

[10]

Chang, Z, Yang D H, Bu X H, et al. Adv. Mater., 2015,27: 5432-5435 doi: 10.1002/adma.201501523

-

[11]

Chen K J, Chen X M, Zaworotko M J, et al. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 2016,55:10268-10272 doi: 10.1002/anie.201603934

-

[12]

Lin R B, Li T Y, Chen X M, et al. Chem. Sci., 2015,6:2516-2521 doi: 10.1039/C4SC03985H

-

[13]

Wang L, He C T, Chen X M, et al. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2017,139:8086-8089 doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b02981

-

[14]

Chen C, Wei Z, Su C Y, et al. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 2016, 55:9932-9937 doi: 10.1002/anie.201604023

-

[15]

Liu D, Chang Y J, Lang J P. CrystEngCommun, 2011,13: 1851-1857 doi: 10.1039/C0CE00575D

-

[16]

Liu B, Yao S, Liu Y L, et al. Chem. Commun., 2016,52: 3223-3229 doi: 10.1039/C5CC09922F

-

[17]

Luo X L, Cao Y, Liu Y L, et al. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2016, 138:2969-2972 doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b00695

-

[18]

Yao S, Wang D M, Liu Y L, et al. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2015, 3:16627-16631

-

[19]

Philipp M F, Wisser V B, Stefan K, et al. Chem. Mater., 2015,27:2460-2467 doi: 10.1021/cm5045732

-

[20]

Li C, Ge H, Li J L, et al. RSC Adv., 2015,5:12277-12286 doi: 10.1039/C4RA10808F

-

[21]

Zhang Z X, Ding N N, Zhang W H, et al. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 2014,53:4628-4632 doi: 10.1002/anie.201311131

-

[22]

John E C, Jason R P, Cameron J K, et al. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed., 2014,53:10164-10168 doi: 10.1002/anie.201402951

-

[23]

Lu Z Z, Zhang R, Zheng H G, et al. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2011,133:4172-4174 doi: 10.1021/ja109437d

-

[24]

Yoshihiro Y, Yuya H, Takahiro I, et al. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2010,132:9555-9557 doi: 10.1021/ja103180z

-

[25]

Vagin S I, Ott A K, Rieger B, et al. Chem. Eur. J., 2009,15: 5845-5853 doi: 10.1002/chem.v15:23

-

[26]

Bu X H, Liu H, Shionoya J, et al. Inorg. Chem., 2002,41: 1855-1861 doi: 10.1021/ic010955y

-

[27]

Xuan Z H, Chang Z, Bu X H, et al. Inorg. Chem., 2014,53: 8985-8990 doi: 10.1021/ic500905z

-

[28]

Chang Z, Zhang D S, Bu X H, et al. Inorg. Chem., 2011,50: 7555-7562 doi: 10.1021/ic2004485

-

[29]

Peter H D, Mary E W, Charlotte L S, et al. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2010,126:12989-13001

-

[30]

Suh M P, Moon H R, Lee E Y, et al. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2006,14:4710-4718

-

[31]

Sheldrick G M. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A: Found. Crystallogr., 2008,A64:112-122

-

[32]

Spek A L. J. Appl. Crystallogr., 2003,36:7-13 doi: 10.1107/S0021889802022112

-

[1]

-

-

扫一扫看文章

扫一扫看文章

计量

- PDF下载量: 2

- 文章访问数: 771

- HTML全文浏览量: 71

下载:

下载:

下载:

下载: